Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Will automation lead to fewer jobs in 10 years? Short answer, yes.

Automation is an elephant. It’s been marching forward at a steady pace for two hundred years, give or take. For the vast majority of these centuries, real wages and economic growth have gone hand in hand with expansion of machine labor. Yet the proportion of adults participating in the US labour force recently hit its lowest level since 1978. In the 1960s only one in 20 men between 25 and 54 was not working. According to Larry Summers, a former American treasury secretary, in ten years the number could be one in seven. So why? What has been different lately?

Automation is an elephant. It’s been marching forward at a steady pace for two hundred years, give or take. For the vast majority of these centuries, real wages and economic growth have gone hand in hand with expansion of machine labor. Yet the proportion of adults participating in the US labour force recently hit its lowest level since 1978. In the 1960s only one in 20 men between 25 and 54 was not working. According to Larry Summers, a former American treasury secretary, in ten years the number could be one in seven. So why? What has been different lately?

The funny thing is that, from an outsider’s perspective, unemployment isn’t an issue now. We’ve just gone through 57 straight months of job creation Yet, post-recession, almost none of these jobs are middle-income. Half the 7.5 million jobs lost during the recent recession were in midpay industries paying $38,000 to $68,000. Only 2 percent of the 3.5 million jobs gained since it ended in 2009 are in midpay industries. Nearly 70 percent are in low-pay industries, 28 percent in industries that pay well. You might be thinking that this is just how recession recoveries work, but you’d be wrong; After the four previous recessions, at least 30 percent of jobs created – and as many as 46 percent – were in midpay industries. That’s big news.

The History of Tomorrow: Why the Luddites were Wrong.

The question of income inequality and job creation/destruction is intimately tied to automation. However, the correlation is not 100% clear. The economics of automation state that if it’s cheaper to install a factory robot or algorithm instead of a human worker, that’s what company owners are likely to do. Historically, when that’s happened, it’s created new jobs for humans elsewhere in the company or economy, usually doing higher-wage work. The word ‘luddite’ comes from early textile workers who sabotaged looms because they felt their jobs were threatened. Clearly, luddites were wrong; the unemployment rate now is fairly similar to what it was before looms entered factories in 1811. The “luddite fallacy” refers to the misconception that automation will lead to widespread joblessness, and, as the word ‘fallacy’ implies, has been pretty much untrue. However, it is based on 2 assumptions: 1) Machines are tools workers use to be more productive, and 2) The majority of workers are capable of becoming machine operators. In other words, machines will always need human oversight, but if they can stand in for workers, and it takes a tremendous amount of skill to be the overseer, displaced workers will struggle to find better work. In this case, we might actually see rising permanent unemployment.

Education is the counter-force to technology, racing against each-other so that workers can find job security as automation encroaches. The problem is that, these days, jobs created by automation aren’t in managing robotic factories. They’re in positions that require a great deal of skill. You can’t just hop from the automated career to the newly created one; the skill sets can be entirely different. People who’ve lost jobs recently in, say, data key entry are not prepared to jump to the high-skilled side of automation, as big data analysts. The subject of the work (data) might be the same, but little else is.

Our Robot Brothers in the Workplace

Regarding our natural advantage- that machines are good at some things, and humans others, it’s safe to say that idea is oversimplified; a decade ago, we were certain that machines could never drive in traffic, and yet Google’s self-driving car emphatically proves otherwise. IBM’s Watson proves neural learning networks and next generation computing will gnaw away at peoples’ advantages in insight generation and learning new tasks, albeit slowly. Slowly is the secret word- replacing a person with an algorithm might be cheaper, but it often requires industries and practices to be reshaped; for instance, harnessing Watson in the field of healthcare will force remaining doctors and practitioners to rely on its strengths to supplement theirs, which is a timely shift.

On a side note, Google’s suggested autocomplete when I searched IBM Watson was ‘jobs’, and IBM’s page listing openings on the Watson team is a fascinating place to gain insight on the jobs neural learning networks create. Almost none of those jobs existed a decade ago. Outside of intern, they’re all high-paying, high-skill jobs, in which 1 worker can have a massive impact. (Actually, the intern gig pays quite well too, around $24 an hour).

People who do manage to get in on the high end of the labor market are making more and more money than the less trained; the gap between median earnings for people with a high school diploma and those with a college degree (adjusted for inflation) was $17,411 for men and $12,887 for women in 1979; by 2012 it had risen to $34,969 and $23,280. There are other arguments explaining the growth of income inequality, the most popular being that if the return on capital is greater than growth in wages, ( R > G ) rich people just get richer faster. But that could just be a macroeconomic perspective about what this new automation enables: people who own robots or algorithms are pocketing the savings automation creates as higher capital returns. According to Erik Brynjolfsson at MIT’s Sloan School: “My reading of the data is that technology is the main driver of the recent increases in inequality. It’s the biggest factor.”

Unspoken Agreements between Humans and Computers

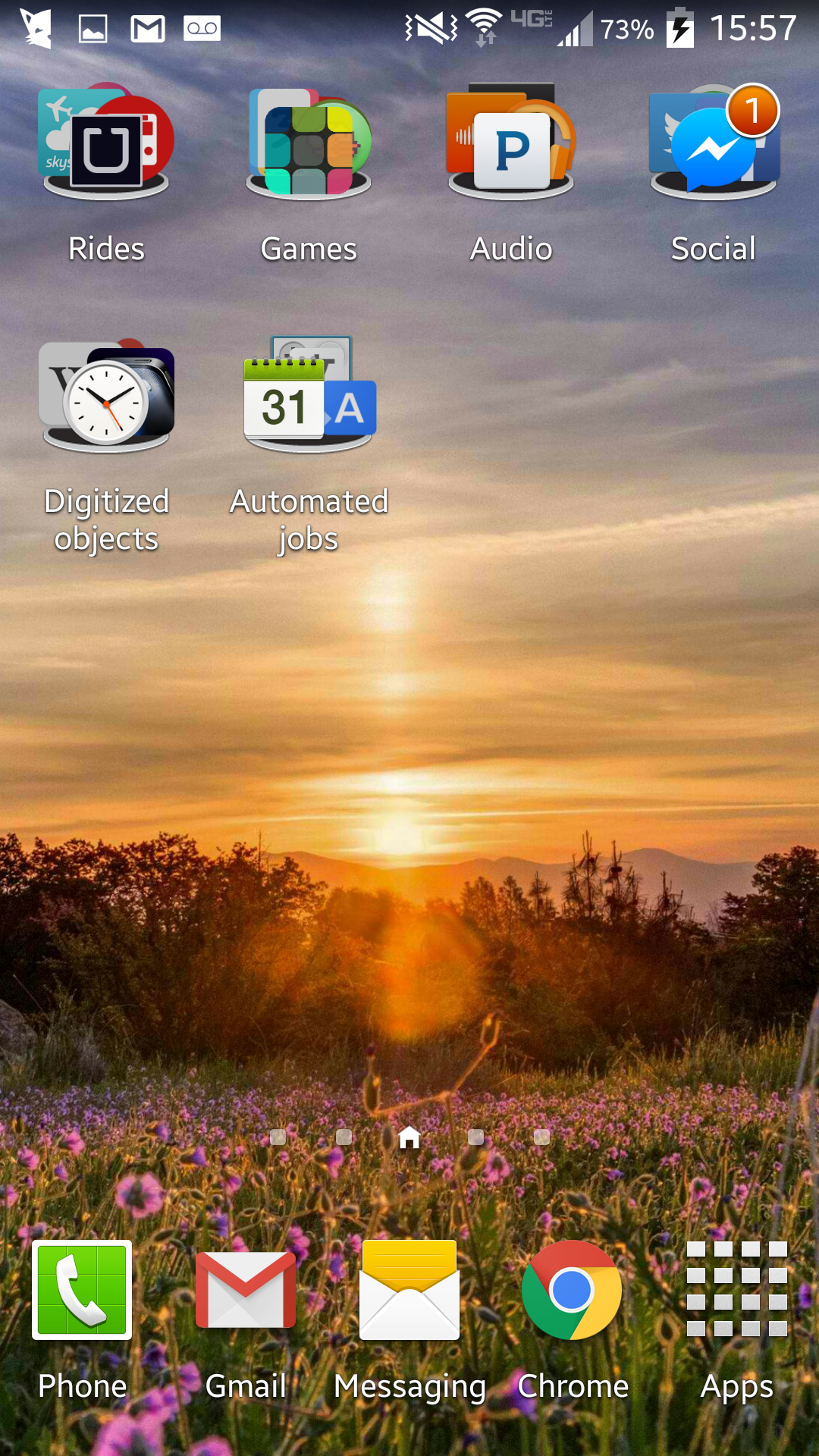

I came across the obvious counterargument recently that we don’t see robots just walking around doing human jobs. Automation these days is mostly about algorithms, not robots though; 20% of HR professionals say they’ve replaced human workers with software; (68% of those 20% also said that this has created new jobs managing those services.) Just look at the apps in your phone, if you need proof of automated job in your daily life; I did.

I came across the obvious counterargument recently that we don’t see robots just walking around doing human jobs. Automation these days is mostly about algorithms, not robots though; 20% of HR professionals say they’ve replaced human workers with software; (68% of those 20% also said that this has created new jobs managing those services.) Just look at the apps in your phone, if you need proof of automated job in your daily life; I did.

Of course, all of these apps require me to do some of the work- for example, enter the text I need translated. It’s part of my unspoken agreement with my machine. So we do have robots that have replaced jobs, and we encounter those robots almost constantly throughout the day.

So what’s the conclusion?

The economy is bifurcating between high, high skill and low, low wage. There will likely be fewer good careers to go around unless our education system can figure out how to prep large numbers for high-skill work. Implementation of automated systems will likely spike in the recovery after our next recession, as HR professionals are tasked with managing a fattening budget and choosing between automated systems and hiring costlier human labor. The upside is that this will all happen slowly, much more slowly than fear might dictate. Systems take a long time to change, and you can’t just plop a robot into a cubicle.

This is where the economics get weird: It’s said that Henry Ford II once showed Walter Reuther, the leader of the United Automobile Workers, around a new automated car plant. “Walter, how are you going to get those robots to pay your union dues,” said Ford. Reuther quickly replied, “Henry, how are you going to get them to buy your cars?” Many companies I’ve spoken to are focusing growth on emerging markets, in South and Central America and mostly Asia. In many of these places, the middle class is actually growing. But as we’ve seen, in the long run, that’s not a sustainable strategy for anyone.

....

This post is the 2nd in a series exploring the changing nature of work leading up to the release of The Future of Youth Employment Report in partnership with Rockefeller Foundation. To learn more about IFTF's Future of Work research initiatives, click HERE. To read the first post, on 3 Invaluable Work Skills for 2018, click HERE.