Future Now

The IFTF Blog

What if health care came with a warranty?

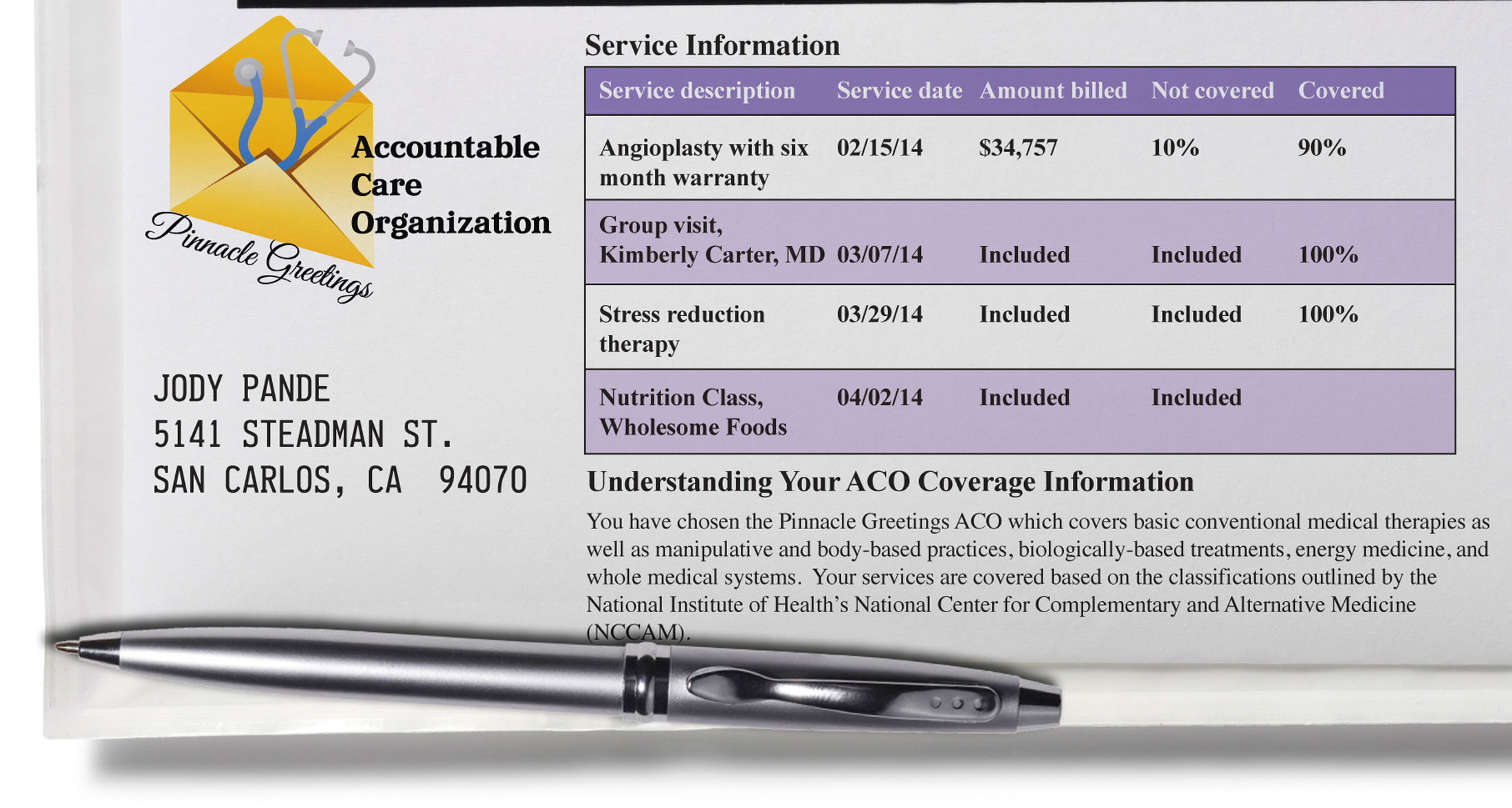

The year is 2014. Jody has just experienced his first heart attack, at the age of 56. According to the latest guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, a man Jody’s age will benefit just as much from an angioplasty as from a more expensive bypass surgery. His doctors perform the angioplasty, following the latest safety protocol from the Institute of Medicine. Thanks to these guidelines, deaths from preventable medical errors have dropped from 100,000 in 2008 to just 10,000 in 2014.

What’s more, after leaving the hospital, Jody’s follow up care is covered as part of the initial angioplasty. This is because Jody is a member of Pinnacle Greetings, an Accountable Care Organization that offers a six month warranty with all angioplasty. Pinnacle Greetings will lose money if Jody winds up back in the hospital in six months with another heart problem. So in addition to the group visits that Jody has with his doctor, he takes nutrition classes and is undergoing stress reduction therapy. After a year, not only has Jody not suffered a relapse, but he has gotten better. He has lost weight, lowered his cholesterol, and improved his overall feeling of well-being.

Jody’s experience illustrates IFTF’s forecast of bundling payments and care, which states, “Payments will be grouped together and linked to patient outcomes to encourage better coordination and communication, resulting in improved quality of care.” This was one of the forecasts in our Health and Health Care 2020 Map, which we recently released publicly.

Bundling payments and care is the combined policy and market response to the perpetual challenge of ensuring affordability and value. It forecasts a future in which we have moved away from the 9000 billing codes now in existence for individual health care procedures, services and separate units of care– and moved toward a system, as Dr. Atul Gawande explained in his June 2009 piece in the New Yorker, in which someone or some entity is accountable for the totality of care. It’s a future in which relying on evidence-based medicine to identify and deploy best practices becomes paramount, and where care decisions made by a variety of clinicians are bundled and paid for based on health outcomes. It’s a future in which doctors are able to bill for patient improvement. This is a future of accountable and appropriate care.

The goal of linking treatment and payment with outcomes is to encourage caregivers to use appropriate medical care for any given condition. This doesn’t mean creating hard spending caps or denying needed treatments; the aim is to eliminate waste, ineffective treatments and to stop spending so much money on medical care that doesn’t work. New benefit structures, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), will scrap fee for service payments and eliminate excessive billing codes, which, in turn, will encourage doctors and hospitals to coordinate and collaborate more closely on patient care.

By the way, the concept of an Accountable Care Organization was developed by Dr. Elliott Fisher at Dartmouth Medical School. Dr. Fisher leads the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care which documents rather striking variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the United States. Since his 2007 paper in Health Affairs in which he laid out the basic structure for an ACO, the idea has gained slow but steady momentum, with more researchers evaluating the promise and the potential of a system of ACOs. See here.

As reasonable and straight-forward as appropriate and accountable care in health care might seem upon first glance, changes to our payment system—from the most radical to the most modest-- have always brought with them both the intended and the unintended consequences.

Consider, for instance, patient selection in a system where payment is based, to some extend, on the health outcome of the patient. Let’s say that Pinnacle ACO is paying Jody’s medical team based on outcomes and that they give bonuses to doctors whose patients have low mortality and complication rates. This raises a bit of a problem, since a medical team can only do so much. They can follow all the best practices in the world, and that will help improve the odds that Jody gets better, but doctors don’t put stents into healthy people. By definition, someone in Jody’s shoes is a big risk—and if he looks like too big a risk because he has other diseases, or because he’s indifferent to his health, some doctors might be tempted to avoid treating him at all. After all, why lose money on a guy who doesn’t care about his health and won’t put any effort into getting better?

Another option is to pay for following the most recent evidence-based protocol, which could help solve the patient selection issue. Rather than getting paid for what they can’t control—like whether Jody decides to exercise and get healthy or watch television and eat cupcakes—an ACO could pay a doctor based on how well she adheres to processes like administering antibiotics at the right time. Setting aside the challenge of selling this to doctors, who mostly practice in solo practices or in groups of two or three and are notorious for resenting “cookbook medicine” and other system directives, sticking to the evidence presents its own set of problems. Patients, or people, will be reluctant to follow strict evidence-based protocol.

Polls have shown that both doctors and people believe that overutilization of medical services is driving up costs without doing any good, but those same polls show that most people do not believe that they, themselves, have received excessive medical care. So like most Americans, if Jody gets diagnosed with a serious disease like cancer he’ll go home and Google it. He’ll look at Wikipedia. He’ll poke around social networking sites. He’ll see that someone in Iowa says their husband’s cancer was cured with an experimental surgery and urges every other stomach cancer patient to ask their doctor about it. In Jody’s case, if his doctor is being paid for practicing evidence-based medicine, when he gets to the doctor, his doctor will likely says no because the evidence says this isn’t the appropriate care. This will lead to fighting and frustration—and potentially some sort of backlash against evidence-based medicine.

Over the next decade, be prepared for more consequences, intended or not, as the forecast of bundling care and payment plays out. Already, warranties to cover avoidable complications following care procedures are now being offered by a small number of US health facilities. See here. And while not one of the principal tenets in the Affordable Care Act that President Obama signed into law last March, ACOs are mentioned. Beginning in 2012, there are incentives for physicians to join together to form Accountable Care Organizations.

Discuss this post on Twitter @IFTFHealth.