Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Thought for the Future of Food

In late September, I shared our food futures research at Five Thot's Idea People Thinking: Food event. From the relationship between social media and wine to the political economy of food trucks, it was a jam-packed evening of stories, inspirations, and provocations for food enthusiasts to think about food in new ways.

In late September, I shared our food futures research at Five Thot's Idea People Thinking: Food event. From the relationship between social media and wine to the political economy of food trucks, it was a jam-packed evening of stories, inspirations, and provocations for food enthusiasts to think about food in new ways.

The event wasn't recorded, but you can read my talk below.

The Future of Food at Idea People Thinking: Food

There’s no denying that our food culture transformed with incredible speed over the last century. Joyce Goldstein’s recent book about California’s food revolution recounts how, as recent as 1981, prep cooks and chefs across Northern California had never seen chanterelles. In 2014, we take mushroom foraging classes and buy kits to grow our own. And these changes extend beyond the Bay Area to around the world, even to change the way we talk about and think about food. Food studies expanded from nutrition and food science to sustainable food systems, gastrodiplomacy, and food anthropology—enticing enough to lure this accountant into a new career path.

Yet not everyone benefits from these changes. Even in San Francisco, a leader in the nation’s food culture shifts, as many as 225,000 people go hungry, while the city collects more than 600 tons of compost, much of it food waste, every day.

Institute for the Future wanted to understand how food experiences are starting to change—and must change—if we are going to build more a more resilient and equitable future. If food and how we think about it could change so drastically in the past 30 years, what potential do the next decades hold? Foresight is about adopting a systems approach, looking beyond food itself to social and technological contexts for change. It’s important, with all the investment in food entrpreneurship and growth in people who really want to make change, to put the conversation in the context of long-term futures thinking and long-term impacts.

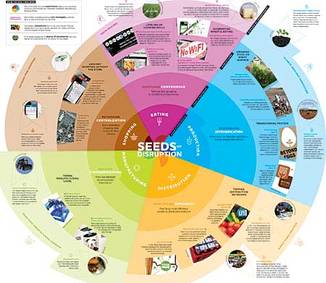

We started by looking at what core strategies drove the global food system to where we are today, and found that they are encountering limits, from environmental degradation to rampant food waste. We looked at ways new technologies could help us transcend these limits. We created a map, Seeds of Disruption: How Technology is Remaking the Future of Food, to tell this story. In the coming year, our research will take us deeper inside these limits, looking beyond just technologies to ways in which new social behaviors, policies, and ways of thinking are combining to transform the future of food. Tonight I’ll share with you three areas from our map where technology is reshaping food and our food culture—and challenging our assumptions about what’s possible.

We started by looking at what core strategies drove the global food system to where we are today, and found that they are encountering limits, from environmental degradation to rampant food waste. We looked at ways new technologies could help us transcend these limits. We created a map, Seeds of Disruption: How Technology is Remaking the Future of Food, to tell this story. In the coming year, our research will take us deeper inside these limits, looking beyond just technologies to ways in which new social behaviors, policies, and ways of thinking are combining to transform the future of food. Tonight I’ll share with you three areas from our map where technology is reshaping food and our food culture—and challenging our assumptions about what’s possible.

Production

Let’s start with production. For the past 50 years, we’ve achieved the greatest agricultural yields in history. But highly intensive production, especially of staple foods like corn and grains, is not without costs. Intensive production means we shifted our focus away from managing natural resources to a dependence on chemicals and engineering for high yields. We are just beginning to understand the consequences of industrial agriculture, from animal waste to fertilizer runoff. Intensified production also means we’ve focused on depth, not breadth, producing only varietals with high yields, rather than a spectrum of flavors, colors, and types previous generations enjoyed.

What if technologies, and more importantly an ecological understanding of how to use them, could refocus our quest for abundance? What if we found new ways to manage agricultural inputs, such as light, water, soil, and air, so that our focus on abundance shifts from increased yield of a few crops to increasing the number of ways and places in which we grow a wider variety of food.

Agricel, a company based in Dubai, is working on a low-water, almost-no-soil solution that allows for less-intensive growing indoors or outdoors. The team developed a water-soluble, biodegradable film, similar to the look of plastic wrap. Roots attach to the film, which acts as a reservoir for water and nutrients. As they grow, the film eventually dissolves into the ground. This system, called film farming, results in up to 90% less water, 80% less fertilizer use, and helps prevent pathogens from entering food as it grows since the film only absorbs water and a few nutrients. Think of the potential to use film farming on rooftops or areas with little water or soil.

In the face of rapid urbanization, IFTF thinks that today's urban challenges point us to urgent futures. Imagine the possibilities of low-resource technologies such as film farming in dense urban settings. We'll be able to grow food in schools, libraries, or even in unused old bomb shelters, like a group is doing in London with LED and hydroponic technology.

In the face of rapid urbanization, IFTF thinks that today's urban challenges point us to urgent futures. Imagine the possibilities of low-resource technologies such as film farming in dense urban settings. We'll be able to grow food in schools, libraries, or even in unused old bomb shelters, like a group is doing in London with LED and hydroponic technology.

Yet attempts to simulate nature can give us a false sense of control and food security, and might further disconnect us from our food roots. California farmer Mas Masumoto, whose deliciously sweet peaches grace the shelves of Bi Rite and Berkeley Bowl once a year, says in his memoir, “… no good farmer can escape contact with the earth … I work my fields according to the dust.” After years, he can anticipate the quality of the crop based on the taste and feel of that year’s dust. New production technologies should not attempt to replace this grounded knowledge, but rather complement longstanding practices and help ensure widespread food security in the context of a larger ecosystem.

Manufacturing

Second, we can look at changes in manufacturing, large-scale food processing. Consistency of taste and texture was a 20th century breakthrough. The fact that McDonald’s French fries look and taste the same year-round is a feat of years of research and refinement. However, this mass standardization is also made possible by additives and preservatives, and optimized for scale and long shelf lives. In response, grassroots efforts promote buying locally, but what if we shifted the conversation away from buying locally to making locally? What if the food industry saw people as makers, not consumers, and brought processes closer to them?

3D printing is a technology that could enable such a transformation. Researchers and adventurous DIYers are developing ways to 3D print things like chocolate, pasta, and confections with remarkable results. What’s more, manufacturing processes once held proprietary are going open source. Underground Meats, a small charcuterie maker in Wisconsin, is developing an open source guide to dry meat curing, intended to lower the barriers to entry for small-batch makers. Imagine that, instead of buying foods produced in a factory far away, you could go your local grocery store’s 3D printing shop to formulate your recipe—whole wheat, gluten-free, or spinach—and see your food being made before your eyes. Or, you might download a recipe from an open source guide to print on your own. This sounds far off, but consider that public libraries around the US are adding makerspaces, and Makerbot printers are already on sale at Bay Area Home Depots.

I’m not talking about replacing artisan production, but instead acknowledging an opportunity for the food industry as a whole to offer more transparent processes, personalized taste and nutritional profiles, and less need for additives and preservatives. A movement from factory to localized manufacturing would reshape how the food industry views its relationship with eaters, to reinforce a more personal connection with food while potentially reducing packaging and food miles.

Eating

Eating is also changing. For decades, the food industry focused on speed and convenience. But studies show that the less time we spend preparing our food, the more pounds we pack on. New technologies can help re-engage people with food in ways that maintain convenience.

Nomiku makes sous vide cooking fun, and some recipes are more convenient than the original. I’ve used a Nomiku to make lemon curd, and it’s much easier to put the mixture in a water bath than stir over a double boiler for 15 minutes—and the result is just as delicious. In addition to new cooking technologies, new sensory feedback tools will help us reinforce positive habits in subtle ways—even changing the simple eating utensil, a technology we’ve used for centuries. HapiFork is a new smart fork that monitors eating habits and vibrates to subtly remind you to eat more slowly.

Nomiku makes sous vide cooking fun, and some recipes are more convenient than the original. I’ve used a Nomiku to make lemon curd, and it’s much easier to put the mixture in a water bath than stir over a double boiler for 15 minutes—and the result is just as delicious. In addition to new cooking technologies, new sensory feedback tools will help us reinforce positive habits in subtle ways—even changing the simple eating utensil, a technology we’ve used for centuries. HapiFork is a new smart fork that monitors eating habits and vibrates to subtly remind you to eat more slowly.

Last year, Psychological Science published four experiments that showed rituals, no matter how simple, make us savor, value, and enjoy our eating experiences. Nomiku introduces new cooking rituals for its growing community of sous vide experimenters, and HapiFork can restore rituals of commensality—eating together—and slowing down to enjoy a meal together. I love seeing that people are developing and using technology to restore food experiences as a valuable part of everyday life.

There’s currently a surge in people interested in the future of food, from National Geographic’s special series to next year’s World Expo in Milan. Yet as far back as 1825, politician and gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin wrote in his famous book, The Physiology of Taste, “the destiny of nations depends on the manner in which they are fed.” We've known for a long time that thinking about food is essential to thinking about the future, and we have a choice in the kind of future we want. We can choose to see food as a means for productivity and profitability or an enabler of community and connection to our bodies, each other, and the earth. As idea people, I challenge you to reconsider your relationship with food, and help others do the same. Our future depends on it.

This post is part of IFTF’s food futures research, which brings systematic futures thinking to food system efforts around the world. Our long-term view encompasses multiple scales, levels of uncertainty, and radically different possible futures. We develop foresight to help others develop insight and take action toward impactful, transformative, resilient change.For more information about our research, sponsorships, collaborations, and events, please contact Rebecca Chesney at [email protected]