Future Now

The IFTF Blog

The Rise of Computational Propaganda

A conversation with IFTF Fellow for Good Sam Woolley

An interview by Mark Frauenfelder

On January 17, 2014, Girl 4 Trump USA joined Twitter. She was silent for a week, but on January 24, she suddenly got busy, posting an average of 1,289 tweets a day, many of which were in support of U.S. President Donald Trump. By the time Twitter figured out that Girl 4 Trump USA was a bot, “she” had tweeted 34,800 times. Twitter deleted the account, along with a large number of other Twitter bots with “MAGA,” “deplorable,” and “trump” in the handle and avatar images of young women in bikinis or halter tops, all posting the same headlines from sources like the Kremlin broadcaster RT. But Twitter can’t stop the flood of bots on its platform, and the botmakers are getting smarter at escaping detection.

What’s going on? That’s what Sam Woolley is trying to find out. Woolley, who joined Institute for the Future as a Research Director, was the Director of Research at the Computational Propaganda Project at Oxford University. We asked Sam to share highlights of his research showing how political botnets—what he calls computational propaganda—are being used to influence public opinion.

What is a bot?

When I speak about bots in the context of the Computational Propaganda Project, or my other work on disinformation, what I’m usually speaking about is social bots, which are a special type of automated software program that runs a profile on social media or that automates a profile on social media. We coined the term “political bots” and we’re interested in social bots that do political things online.

How does a bot actually work? How does it write coherent sentences, and craft messages intended to promote a specific agenda?

There are different ways a social bot can be constructed. One of the things you can do is build a bot that accesses repositories of information, so the bot can be linked to a series of phrases that the programmer has pre-written. The bot can say, “What do you think about this?” And then link to an article. Maybe the article’s from Breitbart, or from MSNBC, with the goal of sharing particular news. That’s a fairly rudimentary way of programming a bot. The other thing you can do is build bots that aren’t meant to communicate on the front-end with people at all. Rather, they’re built to do what we call “passive interaction” with particular profiles. Those types of accounts do nothing but retweet content on Twitter. They’re built specifically to be sold to a bidder that then uses them to retweet their content.

How effective are bots at fulfilling their purpose?

There’s certainly a spectrum of effect. During the U.S. election, for instance, bots were able to infiltrate the highest levels of social media influence by interacting with accounts that we know to be human accounts, and that we know to be retweeted and liked and followed and interacted with by lots and lots of different people. Those accounts often interacted with bot content, retweeting bot-related content. The bots were active members of that person’s social sphere and network. We know that bots can absolutely have an effect on the communication processes that happen during an election. They can be used to inject information into the dialogue.

Another way that bots can be used is to take up a particular conversation topic or to support a particular person, candidate, or idea, in order to create something I call “manufactured consensus.” Basically, the bot, or botnet—which is a collection of social bots in this case—is massively boosting a topic. The botnets leverage their computational advantage to post thousands of times faster than a human could, boosting a hashtag or a topic or a person to make them look much more popular than they are. And oftentimes, what we’re seeing is that Facebook’s news feed will pick up that topic because it thinks it’s real traffic and shows it to regular people.

There’s an arms race between bots and people who want to stop them.

Yeah, there is. It’s absolutely an arms race, and to be frank with you, oftentimes the people who are building these accounts are a step or two ahead of the people attempting to detect them, including the social media companies, but also researchers like myself and my team. It can be fairly frustrating. The more common ways of detecting bots, i.e., looking for really low follower numbers, but really high followed numbers, or looking for no Twitter picture, are increasingly becoming obsolete, because people now understand the most basic ways of detecting a bot.

Is it expensive to hire a bot army?

It ranges. You can buy an unsophisticated bot army on Fiverr for a really small amount of money. They will support you, but probably the accounts will be suspended quickly. There’s still value in them. My former colleague, Gilad Lotan, wrote about his experiment buying a really cheap Twitter following. Over time, the bot network fell off, but lots and lots of humans also followed him, so at the end of the day, even though most of the bots got deleted, he had a much larger following because of the illusion of popularity.

The more expensive networks, which you can purchase on the Dark Web or using other mechanisms, including hiring contractors that offer this as part of their kit, can range in the tens of thousands of dollars. Each bot persona will have its own Twitter profile, Facebook profile, a LinkedIn account, and various other accounts associated with it, and the bots will be updated and run by people.

How tied in are these bot developers with organized crime, particularly in Eastern Europe?

They are quite tied in with organized crime. One way we can begin to understand bot networks is to look at money laundering. In Eastern Europe, the people who are building these bots are supported through nefarious means. But there’s also a lot of tie-ins to Southeast Asia, and South America. You can look at this guy, Andrés Sepúlveda, who told people that he had worked for all different governments to sway elections throughout South and Central America. He’s gone on the books about how that works, including using Twitter bots that are absolutely tied in with the criminal underside.

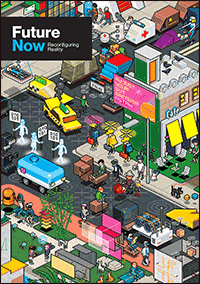

FUTURE NOW—Reconfiguring Reality

FUTURE NOW—Reconfiguring Reality

This third volume of Future Now, IFTF's print magazine powered by our Future 50 Partnership, is a maker's guide to the Internet of Actions. Use this issue with its companion map and card game to anticipate possibilities, create opportunities, ward off challenges, and begin acting to reconfigure reality today.

About IFTF's Future 50 Partnership

Every successful strategy begins with an insight about the future and every organization needs the capacity to anticipate the future. The Future 50 is a side-by-side relationship with Institute for the Future: a partnership focused on strategic foresight on a ten-year time horizon. With 50 years of futures research in society, technology, health, the economy, and the environment, we have the perspectives, signals, and tools to make sense of the emerging future.

For More Information

For more information on IFTF's Future 50 Partnership and Tech Futures Lab, contact:

Sean Ness | sness@iftf.org | 650.233.9517