Future Now

The IFTF Blog

The Livestream Economy

For millions of Chinese, a digital yacht is as good as yuan

Zhao Yue is a typical young livestreaming host in China. Like many women her age, she has a day job, but at night she hosts a simple chat stream from her bedroom. She earns the equivalent of about $600 US a month, and her viewers are mainly middle and high school students. Another young woman, Longlong, was a kindergarten teacher, but in early 2016 she quit her job to become a fulltime livestreamer, renting a kitted-out room from a livestreaming agency and struggling to gain enough fans to make ends meet.

Zhao Yue is a typical young livestreaming host in China. Like many women her age, she has a day job, but at night she hosts a simple chat stream from her bedroom. She earns the equivalent of about $600 US a month, and her viewers are mainly middle and high school students. Another young woman, Longlong, was a kindergarten teacher, but in early 2016 she quit her job to become a fulltime livestreamer, renting a kitted-out room from a livestreaming agency and struggling to gain enough fans to make ends meet.

For millions of people in China, livestreaming is becoming a new form of work. Based on the value of digital gifts their viewers send them, they can earn anywhere from the equivalent of a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars a month. Students are livestreaming from the classroom, ordinary people are broadcasting their dinners out on the town, authors are streaming their book chats, and minor celebrities are becoming major livestream hosts. For the already famous, livestreaming is a way to get closer to their fans and build a relationship that feels more authentic and unmediated. For ordinary people, livestreaming lets them turn their daily lives into a commodity, and find an escape from the crushing loneliness many of them feel.

The year 2016 has been called the “Year of the Livestream” in China. Mobile livestreaming in that country is like a mash-up of YouTube channels, Twitch, Periscope, Facebook Live, reality TV, Snapchat, and Chat Roulette.

New Entertainment, New Currency

Livestreaming apps have become China’s hottest social media craze, generating a burst of investment, users, and new tools. As with many Chinese phenomena, the wave of frenzied interest has resulted in a glut of platforms, a mad rush for differentiation, competition for talent, rising fraud, and increasing government censorship of pornographic or politically sensitive content.

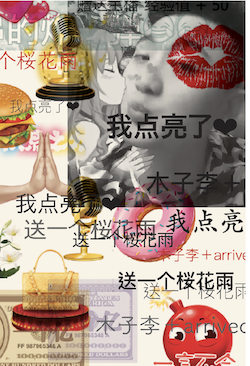

Livestream viewing has become a major source of entertainment for youth, taking the place of time they might otherwise have spent playing video games or watching movies, television, or videos. Mobile apps like YY, Ingkee, Meipai, Huajiao, and Douyu offer tens of thousands of individual channels and have hundreds of millions of viewers. While the apps are specialized for different formats—talk show, seduction, gaming, live music—they all offer roughly the same interaction elements. Show hosts engage directly with viewers via comments, voice, and, most importantly, digital “gifts” whose purchase price creates revenue for the platform and the broadcaster alike. (The split is typically 50/50). These gifts often resemble luxury goods like speedboats, sports cars, and flowers, which are rendered in a cartoon format, and are purely digital, serving as symbols of a cash tribute to the livestreamer. Everyone on the channel sees the gift as it floats onto the screen in real time, and hosts voice their appreciation immediately, with a level of enthusiasm proportionate to the value of the gift. As one young female live-stream viewer noted in a news report, some people spend money on cigarettes; she prefers to spend it on chatting and sending digital gifts to cute, funny boys.

Livestream viewing has become a major source of entertainment for youth, taking the place of time they might otherwise have spent playing video games or watching movies, television, or videos. Mobile apps like YY, Ingkee, Meipai, Huajiao, and Douyu offer tens of thousands of individual channels and have hundreds of millions of viewers. While the apps are specialized for different formats—talk show, seduction, gaming, live music—they all offer roughly the same interaction elements. Show hosts engage directly with viewers via comments, voice, and, most importantly, digital “gifts” whose purchase price creates revenue for the platform and the broadcaster alike. (The split is typically 50/50). These gifts often resemble luxury goods like speedboats, sports cars, and flowers, which are rendered in a cartoon format, and are purely digital, serving as symbols of a cash tribute to the livestreamer. Everyone on the channel sees the gift as it floats onto the screen in real time, and hosts voice their appreciation immediately, with a level of enthusiasm proportionate to the value of the gift. As one young female live-stream viewer noted in a news report, some people spend money on cigarettes; she prefers to spend it on chatting and sending digital gifts to cute, funny boys.

Loneliness is a key motivation behind this new form of interaction. Livestreams, which enable a two-way interaction between host and viewer, offer not just entertainment, but conversation and a comforting sense of being seen and acknowledged by someone else—even if it’s a stranger and for just a fleeting moment. You Could call this “companionship as content.” Livestream viewers are paying for a new form of entertainment with both their cash and their attention. Their participation creates a direct, real-time interaction with the host. They are buying the attention of both the host and the audience.

Experiments Abound

The market for livestreaming is flush with venture capital, at least for the time being, but the massive bandwidth and server costs won’t be sustained by digital gifts alone. Livestreaming efforts underway include:

The market for livestreaming is flush with venture capital, at least for the time being, but the massive bandwidth and server costs won’t be sustained by digital gifts alone. Livestreaming efforts underway include:

- Livestreamed department store visits for consumers to see into Macy’s and GNC’s interiors halfway around the world.

- Livestreamed celebrity shopping trips where viewers can purchase the same items as the famous host.

- Livestreamed tourism, with hosts promoting locations and brands and dispensing digital coupons.

In the years to come, we may see the rise of millions of individual livestream channels supported primarily by voluntary gifts given in proportion to the producers’ ability to deliver sufficient entertainment and “companionship” value to viewers in real time. Just as large companies do today, a new class of personal content producers will use real-time, targeted analytics to tailor what they do to the needs of their audiences.

Just as with Snapchat, Meerkat, and Periscope (the most intimate social media in the West today), livestreaming hosts will experiment with developing niche media audiences. In this future, entertainment genres will be broadened to include all different kinds of live interactions between viewers and content producers, from shared meals and makeup tutorials to DIY reality shows and live daredevil stunts.

Just as with Snapchat, Meerkat, and Periscope (the most intimate social media in the West today), livestreaming hosts will experiment with developing niche media audiences. In this future, entertainment genres will be broadened to include all different kinds of live interactions between viewers and content producers, from shared meals and makeup tutorials to DIY reality shows and live daredevil stunts.

We have seen the rise of “social influencers”—well-known people who partner with brands to commoditize their Internet fame on platforms like YouTube, Vine, and Instagram. Mobile commerce sites like Depop—a type of app-based flea market where people can sell anything from used clothes to bicycles—are helping individuals explicitly create their own branded, curated product channels.

The Chinese livestream model takes this one step further, to a future in which the individual content producer becomes the real-time end node for most products and services, displacing formal stores and websites, not to mention traditional advertising and marketing. When it’s time to buy a new piece of clothing, music, or media, we may see the next generation of young consumers turning first to livestreamers as a searchable database of products and services they can see being used by a real person.

China’s livestreaming market is a test bed for the next decade of global media, blurring the social, personal, and commercial in a way that’s changing media revenue models, online socializing, and even the relationships between product makers and consumers. And given the scale of the experiment—hundreds of millions of individuals streaming their lives, and hundreds of platforms trying out new genres, user interfaces, revenue models, and features—organizations whose success demands new forms of communication, shopping, entertainment, brand, or work should be paying attention.

China’s livestreaming market is a test bed for the next decade of global media, blurring the social, personal, and commercial in a way that’s changing media revenue models, online socializing, and even the relationships between product makers and consumers. And given the scale of the experiment—hundreds of millions of individuals streaming their lives, and hundreds of platforms trying out new genres, user interfaces, revenue models, and features—organizations whose success demands new forms of communication, shopping, entertainment, brand, or work should be paying attention.

FUTURE NOW—When Everything is Media

FUTURE NOW—When Everything is Media

In this second volume of Future Now, IFTF's print magazine, we explore the future of communications. In our research process, we traced historical technology shifts through the present and focused on the question, “what is beyond social media?”

Think of Future Now as a book of provocations; it reflects the curiosity and diversity of futures thinking across IFTF and our network of collaborators. It contains expert interviews, profiles and analyses of what today’s technologies tell us about the next decade, as well as comics and science fiction stories that help us imagine what 2026 (and beyond) might look and feel like.

For More Information

For more information on IFTF's Future 50 Partnership and Tech Futures Lab, contact:

Sean Ness | [email protected] | 650.233.9517