Future Now

The IFTF Blog

The Future of Food in 2015

As our country reflected on the State of the Union last night, Edible Startups’ Austin Kiessig, who recently spoke as a panelist at our Open Cities, Open Food research immersion, released his own thoughts on the state of our food system. In his article, Food Isn't Fixed. But We Are Fixing It Now., he provides a great review of some of the social and technological shifts underway and calls 2015 “the year of the future.” At IFTF’s Food Futures Lab we couldn’t agree more. The full text of his article appears below, but we’re especially excited about two of his forecasts:

“The increasingly educated eater"

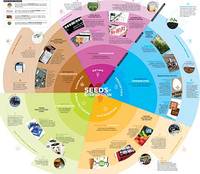

As people seek out more information about their food, it is also important that they understand the future implications of their present day actions. Our public research maps, such as Seeds of Disruption: How Technology is Remaking the Future of Food, can be used by anyone from a food company executive to a college student as a framework to systematically think about alternative possibilities for the future of food. Kiessig raises healthy skepticism about stereotypical food futurism, so we want to expand the conversation: what kind of food futures do you want?

“A better education for food entrepreneurs”

This year, IFTF is partnering with the Bologna-based Future Food Institute and the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia's engineering department for the Food Innovation Program, a 10-month full-time, accredited master's course. With a mixture of IFTF's foresight training, design thinking, and the Reggio Emilia Approach, the course is a unique opportunity to combine long-term strategic foresight with both theory and learning-by-doing in the Officucina, the first hybrid kitchen and makerspace.

So, what will you make in 2015 to create a different future for food?

Food Isn't Fixed. But We Are Fixing It Now

By Austin Kiessig for Edible Startups

2015. It’s hard to believe we’ve marked fifteen years in the new millennium. “2015” feels like that emblematic far-off year in a fantastical ‘80s movie. In that version of now, cars flew (or drove themselves?), eyeglasses displayed our email (oh boy…), and entire meals came in pill form (just add water!). People and planet lived radiantly together. Only alien life forms could screw it up for us.

We now shake our heads at many elements of that dated futurism. Perhaps we scoff most at the idea that fueling our bodies could be as simple as shrinking meals into a capsule. On the surface, not much about the way we nourish ourselves has changed in the past 30 years. Growing food is challenging (scaled indoor agriculture is still in its infancy); waste is huge; our health remains poor; and the war of hearts and minds is brutish (how do you get people to eat their broccoli?). Debate still rages between Slow Food and Silicon Valley; between PETA and Paleo. We haven’t cracked the code on the radical simplification of food. How fanciful, and how American, to believe in the cathartic simplicity of a pill. If only*.

And yet…

Nevertheless, the future for scaled, real solutions has never looked better. There is much reason for optimism as a number of tectonic shifts gather steam. Some elements of the food system (processing innovations, online distribution, the financial ecosystem) are changing relatively quickly, while others (the education of eaters and entrepreneurs, land use, federal policy) are morphing more slowly. However, the direction of progress throughout the Western food system is encouraging. And we all have a role to play in accelerating that progress. As we kick off 2015, let’s explore why.

The Increasingly Educated Eater

The modern history of nutritional science is sordid, indeed. Throughout that history, brash personalities gambled entire legacies on studies and hypotheses that masqueraded as high science, but were really imperfect guesses. Today, the broader population is beginning to coalesce around some of the major questions of diet and health. Excellent scientific journalism by the likes of Dr. Robert Lustig, Gary Taubes, and Nina Teicholz has laid bare the consequences of failed dietary conceits. We now know that the stealthy surge in consumption of metabolically disastrous sugar and processed carbohydrates has created a public health nightmare. We also now know that we shouldn’t have demonized certain fats: evolutionarily, they have always been an important plank of our nutrition, and the links between some dietary fats and both heart disease and weight gain were never as clear as we were made to believe.

These are not middling realizations or fads: we are talking about a fundamental reassessment of the major constituents of the food that undergirds the Standard American Diet. Vegetables are becoming cool again. Portion sizes are becoming (slightly) more modest. Coke, Pepsi, and McDonald’s have experienced stinging contractions in their U.S. business. We’re in the grip of several revolutions in consciousness, layered atop one another. And those revolutions have already engendered dietary shifts that are shaking the foundations of the Western food industry.

A Reconsideration of Food Processing

With more people seeking unprocessed foods, or at least scrutinizing ingredient labels like never before, there is unprecedented pressure on food processors. High Pressure Processing (HPP) has won enormous market share gains in bottled beverages (e.g., the “cold-pressed juice” trend), largely because it is not as destructive to nutritional integrity as pasteurization. Acidified foods are under review as they have been linked to increased prevalence of cancer and acid reflux-related problems. (Important note: not all low-pH whole foods – such as lemons – increase acidity in the body.) Sugar faces renewed investigation as an additive in 80% of foods in the center of our grocery stores. And chemical stabilizers are subject to greater consumer investigation than ever before.

The net effect of all of this is an increased impetus on food processing innovation and greater demand for real foods, delivered cleverly. Food processors that can navigate the intersection of tastiness, health, and convenience will continue to be rewarded. A visit to a major natural foods trade show like Expo West (which had a record 67,000 attendees last year) confirms how many companies are trying to deliver on this promise, and how many eaters and retailers await them.

The Technological Makeover of Retail and Distribution

Over a billion dollars have been invested into food delivery businesses by venture capital in the last 18 months. The traditional brick-and-mortar retail model is under pressure. Think about what this means for us eaters. Instead of relying on monolithic grocery chains to decide which foods are made available to us, we can increasingly turn to online distributors (many of them!) to pick precisely which foods we want delivered to our doorstep. An important bottleneck in food choice is being broadened. As we buy more of our groceries and meals online, our options will proliferate. Upstart products and brands will be able to grow more quickly than ever before. The aforementioned processing innovations will disseminate (and topple incumbents) faster than ever. This is an important spur for transformative food companies that otherwise might have toiled, cash-strapped, for many years to get a shot at a national presence. Now, a multi-region sales profile is not out of the question for a small food business that can navigate the new online sales platforms. This change is great for food producers and eaters alike.

A Better Education for Food Entrepreneurs

The food industry has myriad quirks and considerations that make entrepreneurship tricky. Thankfully, a collection of educational platforms has sprung up to help food founders learn how to build their businesses and mitigate risk. Local Food Lab has been holding startup workshops across the country. Food & Tech Connect has launched a suite of online courses. And the Culinary Institute of America has launched The Food Business School, a full-blown MBA-esque program for food entrepreneurs of all stripes. The combined impact of these programs will be a boost of rocket fuel to an already promising generation of food entrepreneurs.

Changes in Financing for New Business Models

Food is a famously difficult industry for entrepreneurship. Because barriers to entry are low but growth is slow and painstaking, a large number of young food companies fail to progress beyond nascence. Achieving the maturity required to entice institutional investors has been the privilege of a very small fraction (perhaps less than 5%?) of food entrepreneurs.

Yet today, crowdfunding allows packaged food entrepreneurs to finance their businesses in more sophisticated and low-friction ways than ever before. By spreading risk to more investors in bite-sized nibbles of capital, entrepreneurs are able to raise more money earlier, and are simultaneously forced to hone their marketing pitches. More – and better – companies will be able to thread the crowdfunding needle. The result will be better food products for us.

As a case study that brings to life several of the above trends: I was a backer of Exo cricket protein bars on Kickstarter in mid-2013, and last week I was able to buy a case of Exo bars via an innovative new online retailer for health foods called Thrive Market. It dawned on me that Exo has achieved de facto national distribution, less than 18 months after launching via a crowdfunding platform. Five years ago, that would have been nearly unthinkable.

In addition to the very public proliferation of crowdfunding platforms, other financial innovators are changing the way capital is raised and deployed in the agricultural value chain. The firm I recently joined, Equilibrium Capital’s Agriculture Capital Management, has raised a food and agriculture fund that invests in farmland, processing assets, and food product development. The fund has a ten-year life (longer than the five-to-seven year orientation of most venture funds, and much longer than the minute-to-minute outlook of equities traders) and a major focus on environmental sustainability in growing practices and healthy food products. This structure aligns investors, fund managers, and growers/employees around a single vision: to responsibly steward healthy soil, sell wholesome foods, and generate competitive profits. If investment firms like Equilibrium are successful, they will attract larger amounts of capital and invite emulation among other investors. By innovating entrepreneurially in the owner-operator investment model, funds like Equilibrium can create a huge ripple effect in both capital markets and the supply chain for our food. The soil and our bodies will benefit.

Enlightenment at the USDA

I recently had the privilege of spending an hour with Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack. In that conversation, I learned much about the new programs the USDA has launched or is developing. The list of topic areas is impressive: bringing more young people into farming careers; soil and water health; climate change risk management; sustainable land tenure policy; and food waste reduction. Given that the federal government underwrites over $200 billion in loans to the rural economy every year and channels millions more to farms through grants and investment in R&D, it should give us all hope that the USDA is taking a progressive stance on the issues of the day. Let’s all pay attention to and support these programs, and lobby to ensure that they thrive in future political administrations.

The Year of the Future…

In many ways, it’s arguable that the “future” we longed for is already unfolding. The radical transparency of modern life has forced us to ask hard questions about our hard problems. Solutions to those problems have begun to bloom. Positive changes in the food system are real, synergistic, and persistent. As eaters, shoppers, investors, and learners, it is our responsibility to enable this evolution with our choices. We don’t need a magic pill. We just need us.

*While we’re on that topic: I don’t believe Soylent is the “pill” we longed for. It merely modulates the fifty year-old nutrition shake concept, even if it is more scientifically formulated and more cleverly marketed. Soylent can sustain, but it does not nourish, and it does not supplant a real meal protocol. It is a stab at extreme reductionism in the face of an age-old challenge: what to eat, and how to get it? And let’s keep in mind that Soylent’s ingredients still come from plants. So do the ingredients of Hampton Creek,Impossible Foods, and Beyond Meat’s products. Horticulture remains the foundation of our food chain. And horticulture remains challenging.

This article originally appeared in Edible Startups as “Food Isn’t Fixed. But We Are Fixing It Now”

This post is part of IFTF’s food futures research, which brings systematic futures thinking to food system efforts around the world. Our long-term view encompasses multiple scales, levels of uncertainty, and radically different possible futures. We develop foresight to help others develop insight and take action toward impactful, transformative, resilient change.

Interested in learning more?

For more information about our research, sponsorships, collaborations, and events, please contact:

- Rebecca Chesney at rchesney@iftf.org