Future Now

The IFTF Blog

The Caregiver / The Artificial Caregiver

[This article is one of a four-part series in Scenes From 2027]

The Caregiver

What happens when your health is dependent on an upgrade you can't afford?

As intelligent autonomous objects proliferate, they can be seen as empowerment tools to make us more capable and independent. This is especially true in the home and in adaptive aging-in-place centers where advances in mixed reality, conversational, and other intuitive interfaces are supporting caregiving efforts. But as we come to rely on networks of machines provided by different companies for caregivers, how do we ensure reliable service and equitable access?

What

Resurion is a service that offers an integrated aging-in-place system that relies largely on technology that already exists in many homes. The cameras, motion sensors, and microphones found in refrigerators, microwaves, and bathroom mirrors are used to monitor vitals and physical motion. (Those with comparatively pricey smart toilets can add microbial and glucose tracking to the mix.) The service also taps into the lightweight projectors of entertainment systems as well as the augmented reality capabilities of high-end eyewear to detect objects that need attention (meds that need to be taken, food that needs to be thrown out or put away), or make more dramatic changes, like transforming the appearance of an entire room to soothe and reorient those suffering with dementia by transporting them to a familiar setting from the past.

Resurion also provides cheap supplementary components, cameras, and motion trackers for those who don’t have smart appliances, and generic robotic augmentation of chairs, cabinets, and walkers that shuttle objects in hard-to-reach places and transport users to where they need to go in the home. It also gives family members remote surveillance capacities and the ability to virtually drop in, if invited, by the primary user.

So What

By 2027, many common household items will be embedded with sensors, actuators, computing power, and access to powerful cloud intelligence. The true potential of these devices, will be less in their individual capacities, and more in harmonizing the functions and services they provide to create cohesive experiences.

This will be particularly true when it comes to orchestrating technologies to help people age in place. By 2027, older adults will comprise a greater portion of the U.S. population than at any other time in human history. Technologies that help people to become more capable and independent will be in particular demand. Intelligent and connected devices offer many opportunities.

Autonomous objects can be used to monitor people who might otherwise require human supervision, allowing them to retain a sense of privacy and agency. They can also give people greater mobility. Such objects can provide important information resources and emotional support. At the same time, there are huge unresolved questions. How do we ensure a coherent experience across devices provided by multiple companies? When we rely on them for physical and mental health, who is responsible when they break down?

The Artificial Caregiver

A lost childhood toy returns in an unexpected context

A popular aging-in-place service provider has a beloved interface, but security and reliability issues around the third-party devices it relies on is forcing the company to take control—and raise rates substantially, pricing out a substantial portion of its user base.

Maya Burnett lost Deren for the first time in 1962, when she was just 5 years old. He was her stuffed rabbit and her best friend. He had been with her since as long as she could remember. And when she accidentally dropped him down a storm drain while crossing a busy street, it broke her heart.

“I wanted to go down and search for him, but my parents wouldn’t let me,” she recalled. “I cried for weeks.” But Deren was returned to Maya 65 years later, in an unexpected way.

On her 75th birthday, Maya’s family took her to Buscema’s, a franchise Italian restaurant at the Southland Mall in San Leandro, California, to celebrate. After the meal, Maya got up to go to the bathroom—and never came back to the table. Some ten minutes later, Ana, her daughter-in-law, went to check up on her and found nothing but an empty stall. After a brief but frantic search, Maya was discovered trying to “hail a taxi” on the street outside. She had no memory of how she got there. It wasn’t the first time she had displayed signs of dementia. But it was the wake-up call she and her family needed to spur them to seek help. Maya was determined to remain independent and so she, like many others, turned to Resurion, a once promising startup that is now facing closure.

The company offers an integrated aging-in-place system, that relies largely on tech that is already in most people’s homes. The cameras, motion sensors, and microphones found in refrigerators, microwaves, and bathroom mirrors are used to monitor vitals and gait, and track behavioral patterns. (Those with smart toilets can add microbial and glucose tracking to the mix.) It also taps the lightweight projectors in many people’s entertainment systems and augmented reality capabilities of higher-end eyewear to do subtle things, like highlight objects that need attention (meds that need to be taken, food that needs to be thrown out or put away), or make more dramatic changes, like transforming the appearance of an entire room to soothe and reorient those suffering with dementia by transporting them to a familiar setting from the past.

Resurion also provides cheap supplementary components, cameras, and motion trackers for those who don’t have smart appliances, and generic robotic augmentation for chairs, cabinets, and walkers that shuttle needed objects in hard-to-reach places or even transport the user to wherever they need to go. And, of course, Resurion provides family members with remote surveillance capacities and the ability to virtually drop in and inhabit the physical apartment, when enabled to do so by the primary user.

“It’s typical home tech that’s used in most aging-in-place and child-care systems,” Ana Lily Farhadi, Resurion’s design director, explained. “What sets us apart is the interface.”

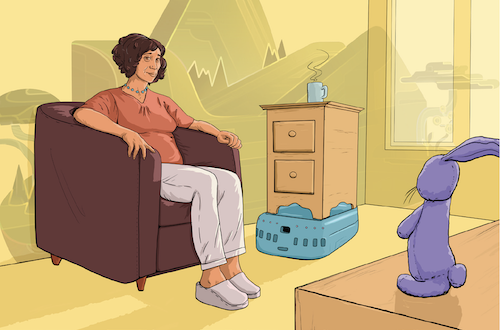

This is how Maya was reunited with Deren. When she signed up with Resurion, she was asked about people and objects in her life that she found comforting and reassuring.

“They told me that for people suffering with dementia, objects from your youth can be the best, and Deren immediately came to mind,” Maya recalls. “I told them, ‘When I was just a girl, I had a stuffed rabbit that I loved dearly.’ And they asked me, ‘Do you have a picture?’”

The next day, a technician from Resurion brought her a disk, about the circumference of a coffee mug, and placed it on her living room shelf. She pressed the only button on the object and, suddenly, a lifelike replica of Deren appeared. She explained to Maya that they had used the photo to recreate Deren running a common algorithm that took the visible parts of the doll and extrapolated what the rest of it might look like. They asked her what his voice should sound likeand, after telling them she felt he might be “British, and a little stuffy,” they assigned him a voice that mimicked that of comedian David Mitchell.

Soon, Deren once again took a central role in Maya’s life. Functionally, he was like any other AI agent. He could speak to Maya through any of the speakers in the home or hear her through any of the microphones. Still, Maya chose to speak to him, for the most part, “in person,” talking directly to the avatar on her shelf. He acts less as a servant and more as a friend, conversing with Maya and even posing puzzles and riddles to help keep her mind sharp.

“We worried at first that she was too dependent on Deren and that the whole thing sort of felt condescending, like we were treating her as a child,” her son reflected. “But she didn’t see it that way, and with everyone working, we came to see him as a minor miracle.

“In fact, in many ways, Mom is much more independent. When it’s not humans doing the surveillance, being watched provides a level of security that’s quite freeing,” he continued. “Deren’s a source of confidence as much as comfort to her, it seems.”

But Maya could soon lose Deren once again. While Resurion orchestrates the actions of all of the various devices its system relies on, it doesn’t own them, so the company is now closing their ecosystem, forming partnerships with trusted vendors and staffing up with workers who can provide continuous support and maintenance. And they’re raising rates by a whopping 200 percent.

“Making the service only available to those who can pay feels like a failure,” Chief Financial Officer Hirokazu Yamashita said. “But we don’t really have other options. We explored ideas like ‘freemium’ models, but ultimately found the tradeoffs were even worse.”

For Maya, and people like her, being priced out could be devastating. And not just for the material impacts it would have in terms of tangible services that Resurion provides.

“Losing Deren the first time really haunted me. For years, well into adulthood, I would occasionally be struck with the image of him all alone, deep underground in the dark sewer. I pictured him slowly deteriorating,” Maya explained. “I know this sounds dramatic, and I don’t mean to be self-pitying … but if I lose him again, the one alone in the dark, deteriorating. Well … that might be me.”

FUTURE NOW—Reconfiguring Reality

FUTURE NOW—Reconfiguring Reality

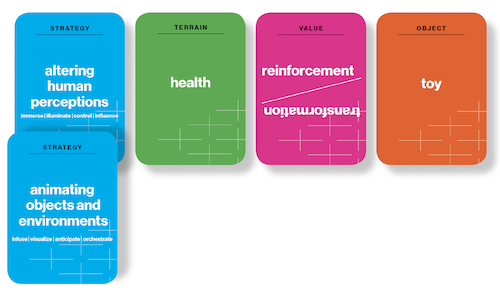

This third volume of Future Now, IFTF's print magazine powered by our Future 50 Partnership, is a maker's guide to the Internet of Actions. Use this issue with its companion map and card game to anticipate possibilities, create opportunities, ward off challenges, and begin acting to reconfigure reality today.

About IFTF's Future 50 Partnership

Every successful strategy begins with an insight about the future and every organization needs the capacity to anticipate the future. The Future 50 is a side-by-side relationship with Institute for the Future: a partnership focused on strategic foresight on a ten-year time horizon. With 50 years of futures research in society, technology, health, the economy, and the environment, we have the perspectives, signals, and tools to make sense of the emerging future.

For More Information

For more information on IFTF's Future 50 Partnership and Tech Futures Lab, contact:

Sean Ness | sness@iftf.org | 650.233.9517