Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Task and Matter Routing for Health

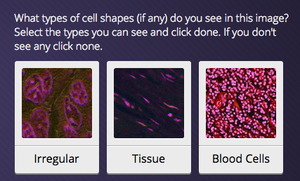

Via Springwise comes word of an interesting project out of the UK called Click to Cure. At its core, the idea is simple: Give people a bit of training and set them loose on a huge set of images of cancer cells in the hopes that their efforts can advance basic R&D. The project's sponsors describe the effort as:

New techniques are revolutionising our understanding, diagnosis and treatment of cancer, but with radical advances in technology come new challenges. We have huge amounts, terabytes, of archive research data that requires urgent analysis; analysis that our scientists are doing everyday. They just can’t get through it fast enough. Although we live in a technological age, our datasets still require analysis by real people and cannot be left to computers alone. It takes human intuition and the human eye to spot patterns, defects and anomalies-computer algorithms just aren’t good enough. The process is slow for a lone scientist, but with the collective power of hundreds of thousands of people, we can speed up this research by years. The faster we can analyse our data, the faster we can unlock its secrets and discover new methods of treatment and detection; and together we will find cures for cancer sooner, rather than later.

It's a signal of one of several new mechanisms for coordinating activities that my colleagues in the Technology Horizons Program highlighted at their great conference earlier this month. This project, an example of what my colleagues called human task routing, points toward an unprecedented ability to take complex tasks--like conducting basic cancer research--and break them into small chunks that virtually anyone can perform.

Our Technology Team also highlighted something they called matter routing, which you can think of the combination of autonomous vehicles and algorithms to enable, in effect, matter to route itself to us. A good signal of this comes from Fast Company, which notes a prototype project aimed at using drones to deliver defibrillators to the exact location of cardiac arrest events, which can (at least theoretically) get to an emergency faster than paramedics--in a situation where saving a minute can literally mean the difference between life and death.

Together, these two signals point toward opportunities to improve upon a couple of basic ideas we have in health. Medicine currently requires incredibly skilled labor--think doctors, ph.d. researchers and so on--whose contributions, as in the case of response to cardiac arrest, are often required unexpectedly, and with incredible speed. These signals point toward a future where the ability to summon support--from the crowd as well as needed resources like defibrillators--will make it a lot easier to satisfy the needs to have expertise and resources available as needed.