Future Now

The IFTF Blog

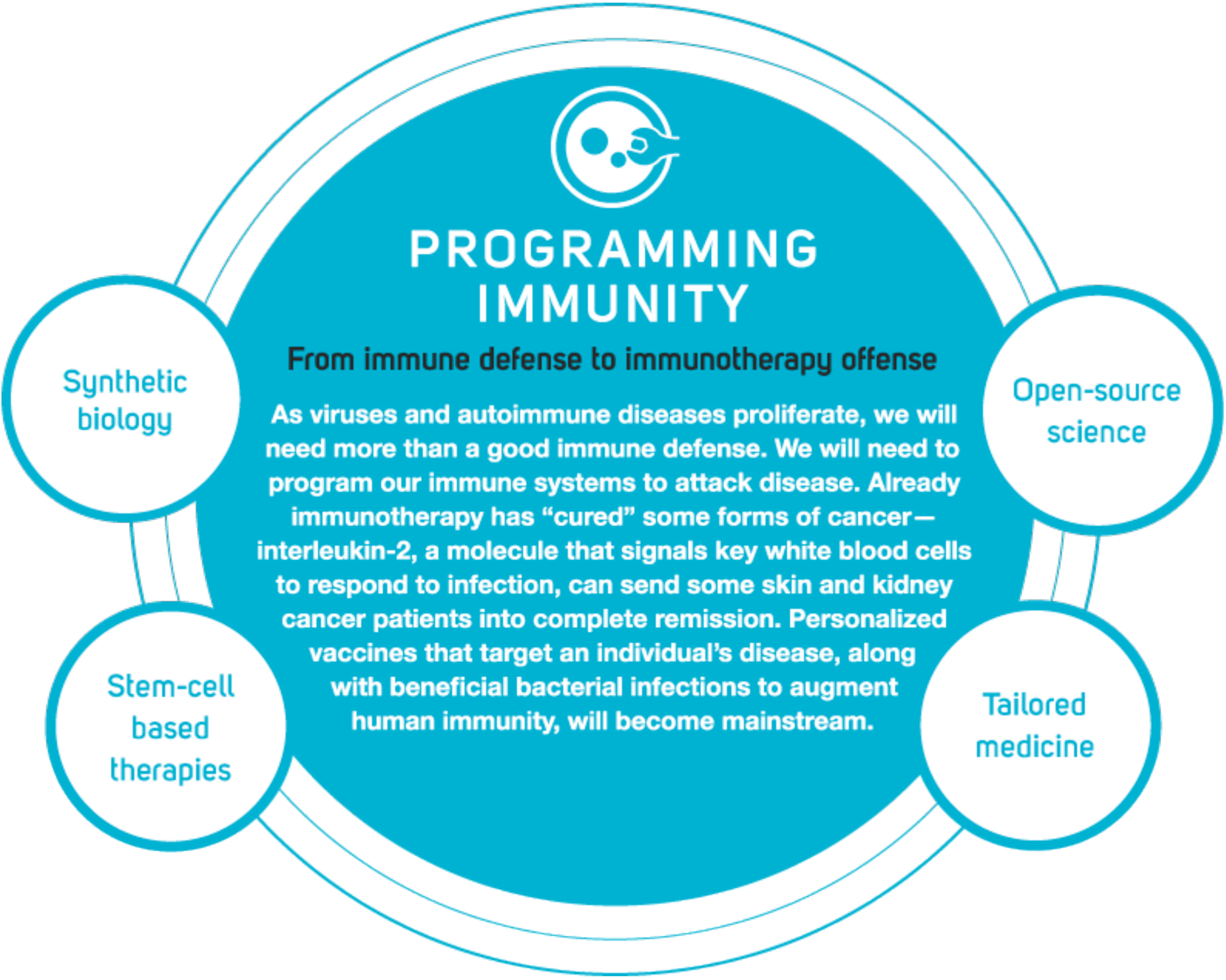

Programming Immunity: Defense to Offense

As we scanned the horizon of science and technology’s ability to create health and well-being, we became fascinated with the idea of tinkering: experimenting with incremental improvements to our selves and surroundings. And one of the bits of our biology we’ll be tinkering with over the next decade is our immune systems.

Our immune systems are the key to humans’ profound resilience in the face of all the other organisms around and inside of us.

Over the last few decades we’ve made great strides in understanding the workings of various parts of our immune systems, as they function normally and as they get jammed up in strange ways. This forecast posits that over the next decade we’ll be able to put this knowledge to striking use: honing our immunomodulation therapies, mainstreaming the maturing promise of gene therapy, and hacking our immune systems to accelerate our resistance to all kinds of infections.

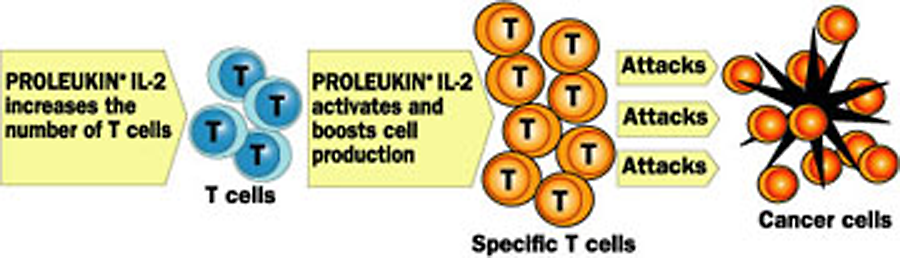

One of the examples used on the map involves reprogramming how our immune systems react to certain conditions, by introducing recombinant versions of the transmitter cells that regulate the relevant immune functions. For instance, the cancer immunotherapy Proleukin (or interleukin-2) uses a genetically engineered version of naturally occurring proteins that make parts of the immune system more or less active, and prompt immune system cells to be more effective. It helps the immune system produce T-cells specifically geared towards recognizing and destroying the cancer cells.

Recently, there was a serious breakthrough in the decades-long promise of gene therapy that takes this a step further. Rather than introducing a modified transmitter protein, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania successfully modified patients’ own T-cells, inserting a gene that re-programmed them to recognize cancer cells as invaders. Not only was the therapy successful for fighting the tumors (two of the three patients went into complete remission, and one improved significantly), but the modified cells persisted in the patients’ bloodstreams, promising to fight the leukemia cells even if they reappeared. (Full text of their research article in Science Translational Medicine here.) While this might sound very experimental, it could well advance very rapidly from here out.

My colleague Alex Carmichael wrote about an even more far-out and mind-bending promise as we were conducting this research.

Kary Mullis, the winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), is on a quest. Mullis wanted to find a faster way - a way to hijack existing immune responses rather than wait for new ones to build up. He was motivated by a worry that the greatest threat to humans in the coming years would come from infectious disease.

So he invented Altermune.

Alex does a great job of explaining the biological processes behind this, and Kary Mulis’ website offers a compelling description of the basic premise:

The Altermune method, taking advantage of the evolutionary skill of our immu

ne system for killing micro-organisms once their structure has identified them as being enemies, is developing the process of building bionic arms for antibodies, which once the offending microorganism is identified, can grab it. The process already is quick and efficient, and shockingly so for the microbes, who are used to the slow creep of biology, and know nothing of nuclear magnetic resonance or high resolution mass spectroscopy.

Bionic arms for antibodies! Seriously folks. This is exciting stuff. Mullis envisions being able to streamline the process of flu vaccination into an inhalable fast-acting immune trigger. One of the most exciting applications he mentions is the ability to target bacteria—even those rapidly evolving out of the reach of our eighty-three-year love affair with antibiotics.

Check out this and other forecasts on our Future of Science, Technology, and Well-being 2020 Forecast Map.