Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Podcast: Black Lives Rising (in STEM)

Why having more black leaders in science and tech will boost America's future

by IFTF Research Fellow Mary Kay Magistad; reposted from Whose Century Is It? on PRI

Here’s one way to think about America’s future in this century. The majority of babies now being born in the United States are of color. They’re Hispanic, black, Asian, Native American, mixed race.

Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

Donald Trump’s tenure as president is not likely to change that, no matter what the white supremacists among his supporters may hope.

The question is — what will he do, as president of all Americans, to help kids of color get a good education, and have ample opportunity to come up through the ranks, adding their ideas and energy to an economy that is, increasingly, knowledge-based? If the answer is not much, or worse — be concerned. Because America will not benefit, as a global leader or as a society, from holding back the potential of half its future workforce.

Of course, some non-white Americans have a harder time breaking the color barrier — especially in cutting edge fields. African-Americans, in 2011, made up 11 percent of the total workforce — pretty close to their actual share of total population. But they made up only 6 percent of STEM workers — that’s, science, technology, engineering and mathematics, the areas where innovations that change lives often happen.

The more diversity there is among the people coming up with those innovations, the more likely they’ll address the needs and challenges of diverse communities, not just of middle class and affluent white guys. Top Silicon Valley companies are among the worst offenders — for many, African Americans make up just 1 percent of their skilled workforce. Apple is doing better — 6 percent of its skilled workforce is African American. Fully 25 percent is Asian.

So as our nation’s first black president winds down his tenure with relatively high approval ratings, the question turns to how to help more African Americans become change-makers and leaders, at a time when a vocal portion of white Americans are already complaining about the non-whites who are taking "their" jobs and changing "their" country.

Want to make American great again? Then look to someone like Joshua Johnson, 18, a freshmen at the University of Michigan, who’s already imagining ways to use his computer skills to empower more people.

Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

"I really want to make software that makes the user interface for coding a lot easier for people, so that people don’t have to go to school and study coding to make a career out of it,” he says. “They can do Khan Academy courses, and grasp the ideas of coding a lot easier than we do now. Make programming available for everybody, you know? I think that will change the world.”

For Joshua, this isn’t an abstract idea. He’s got buddies back home on the South Side of Chicago who he knows to be smart and capable. They went to grade school together, but then Joshua went to a magnet school, and his friends stayed in the notoriously underfunded public schools in the area — and he says though he tried to convince them they could close the gap and do what he’d done, the gap kept getting wider. Now, some of his friends are already parents, at age 18. Others are in gangs.

“The neighborhood where I grew up is colloquially know as 'Killer Ward,'” Joshua says. “It’s got a huge gang presence that drags kids in pretty early. I knew kids in the seventh and eighth grade who were pretty involved in gangs. I think a lot of great potential was lost to that.”

In Joshua’s neighborhood, Englewood, that skill is all too useful. There have been 53 homicides there in the past year alone — in three square miles with 30,000 people. Almost all are African American. One in five adults is unemployed, and half of families live beneath the poverty line.

This is where some people — too many people — are quick to say, "it’s because they’re lazy," or "it’s their own fault; it’s black gang culture that keeps people down." That overlooks the web of systemic and historical reasons why it’s much more likely that an African American born into the lowest 25 percent by income in the United States, is unlikely to rise above it, compared to white Americans. It’s safe to say that systemically entrenched racism has something to do with it.

And sure, sometimes someone like Joshua can study hard, rise above it, and become — as he has — the first person in the family to go to college. He says his mom pushed him, almost from birth, to think of himself as headed for college.

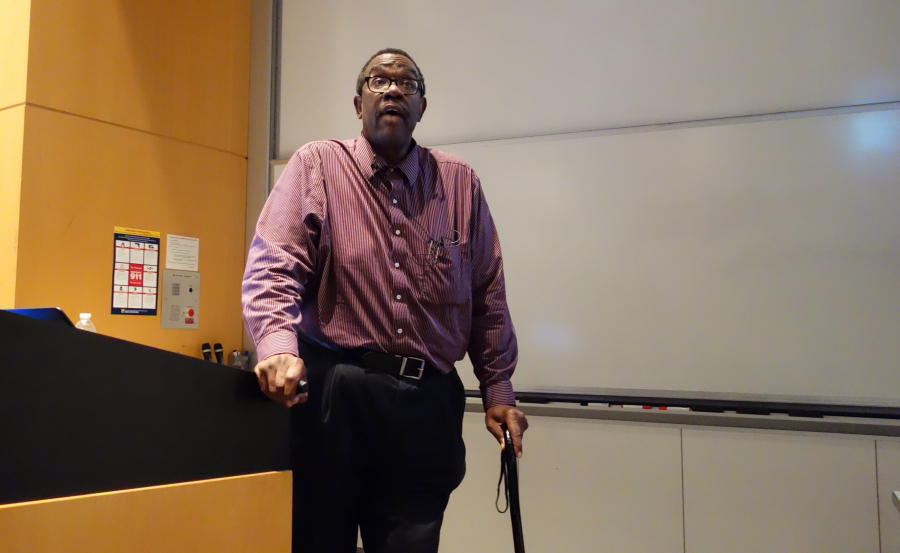

Robert Scott knows how that goes. He says the matriarchs in his family, and a favorite African American female teacher, pushed him, too. He was an engineering student at the University of Michigan four decades ago and, after a long and successful career, including as a senior executive at Procter & Gamble, he’s back, trying to draw more African American kids into STEM fields.

"We no longer live in a manufacturing economy,” he says. “We live in a knowledge economy. And the preparation for being a knowledge worker equates to STEM. I mean I can't say it any more succinctly than that. If you look at where the jobs are, where the opportunities are, where the exciting careers are, they all have a technology focus and bent. So I think it’s critically important for African-American men and women to identify and aspire to top schools in STEM, because that's the way the world is going.”

Scott, these days, is a genial, towering force of nature, aside from a cane he occasionally leans on to favor a bad hip. He jokes with the high school students who come in for STEM summer camps that they can call him “Grandpa,” and many are clearly fond of him. He does more than just make sure young African Americans learn their engineering and tech skills. He tries to prepare them to work, and lead, in a world that’s still far from colorblind.

Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

“If you don’t write anything else down, write this down,” he said to an auditorium of high school students in July 2016, shortly after shootings of unarmed African American men, and then, the shooting in Dallas of police by an African American ex-soldier. “You’ve been socialized, by definition. It’s not a bad thing, it’s just the way it is. The question is, how have you been socialized, and do you know? And can you move that socialization from unconscious to conscious, so that you know how you think, and then learn how to talk and exchange with others, to hear how they’ve been socialized, and what they think and believe, seeking first to understand, and then to be understood. That’s how you have constructive dialogue."

“And let me say, right up front, for people who think Grandpa is a naïve old fool, this ain’t easy. Because if it was easy, this crap wouldn’t be happening. And it’s been happening for decades. It’s been happening for centuries. So, not to despair. It’s our responsibility to work to change this.”

Change has come slowly, and sometimes not in the right direction. The end of affirmative action policies at many campuses, including the University of Michigan, has reduced the percentage of students on campus who are African American.

Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

More broadly, African American families around the country are making less, on average, than they did 15 years ago, and also less as a percentage of what white households earn; black families' median income is about 60 percent that of white families'. Fewer than half of black households own their own home, compared to almost three-fourths of whites. And while the number of African Americans with college and advanced degrees has grown — it hasn’t grown as fast as white Americans getting the same degrees.

In Detroit, as in predominantly African American districts of Chicago and beyond, inadequate funding for public schools has taken a heavy toll. Test scores are among the worst in the nation. More of that may be on the way, as Donald Trump’s pick for education secretary, billionaire Betsy DeVos, is an advocate of taking more money away from public schools, and giving it, in the form of vouchers, to private and religious schools.

The Detroit public school system has already closed many of its schools, lost two-thirds of its students, and has driven some of its best teachers away, through pay cuts and by allowing non-certified teachers to be hired, and for those hiring teachers not to be able to offer higher salaries based on levels of experience or education.

“I'm not sure what the legislature was thinking when they passed those laws. But it is a fact that that's what happened,” says Nick Collins, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Educational Outreach.

Collins says all this makes his job tougher, and the numbers suggest this is a national problem.

“If you look at data, recently reported data, by the way, suggest that of the students who attend the most prestigious colleges and universities in the country, 72 percent of them come from the upper economic strata,” Collins says. “That is families that are in the upper 25 percent, while only 3 percent of students at our most selective colleges come from the lower economic status, that is the bottom 25 percent. That kind of inequality is troubling.”

But for all these problems — and they may get worse in places like Detroit, before they get better — there are some signs pointing in a more positive direction. The Obama Administration has earmarked $850 million over the next 10 years into trying to increase the number of African Americans in STEM studies and jobs, including leadership positions.

And while just 15 African Americans have ever been CEOs of Fortune 500 companies — five of them are now — the percentage of African Americans in the “C-Suite,” CEO, CIO, CTO and so on — has doubled from 3 to 6 percent over the past 20 years.

Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

And as a new generation of African American digital natives rises, Carla Ogunrinde, a former Fortune 100 executive, now chair of the Information Technology Senior Management Forum, which helps mentor African-American senior managers and leaders, says she sees reason for hope.

“We're doing all we can to keep up with their enthusiasm about what they can do, because they always believe that 'I can do anything,’" she says. “It's, like oh my gosh yes you can! You can, [but] slow down. Hang on. And so, it's a wonderful push, pull, because we're learning a lot. This generation, they are very open. It's about reciprocity. It's about well I have this what do you have? And the walls are low. And again, it's a very exciting thing. And it's something to admire. I don't know what the future of that, the impact is. African-Americans used to have a lot of ‘to dos’ to succeed: Keep your head down. Know the game. Know who the players are, and play the game. That's not the advice anymore. ... Now, ideas are king, and it’s a new game.”

Mary Kay Magistad, IFTF Research Fellow and recovering foreign correspondent, is creator and host of the “Whose Century Is It?” podcast, a coproduction with PRI/BBC’s The World, exploring ideas, trends & twists shaping the 21st century. It’s available on iTunes, most podcast apps, and at pri.org/century.