Future Now

The IFTF Blog

PMWC Preview: Cancer Commons

Health Horizons researchers will be attending the 2013 Personalized Medicine World Conference here in Silicon Valley, January 28-29. In the run-up to the conference, we’ll be talking with some of the scheduled speakers to preview their talks at the event. (For more information on the conference itself, please visit the PMWC 2013 conference website.)

We sat down with Marty Tenenbaum, Founder of Cancer Commons, to talk about realigning incentive structures, the importance of creating scientific commons, and the shift toward a new paradigm of patient-centered translational medicine.

Cancer Commons is “a nonprofit organization building Rapid Learning Communities comprising researchers, patients and physicians. We are dedicated to advancing precision therapies by developing a ‘commons’ that collects diagnoses, biomarkers, treatments and outcomes for patients who fall outside the standard of care.”

Tenenbaum, a cancer survivor himself, was frustrated with the unequal distribution of knowledge about treatments. What he saw was, “an immediate opportunity not to cure cancer, but to improve outcomes for individual patients, by getting the right information to the right people at the time they are making decisions.”

As an e-commerce pioneer, Tenenbaum felt he had the necessary entrepreneurship and IT background to tackle the resistance to sharing data, but he knew this would mean “blowing up the existing walls.” These walls are especially strong in the structure of economic incentives, which makes hoarding proprietary data the rational option.

“We are trying to bring everyone to the table in an ecosystem that supports personalized oncology,” Tenenbaum said. “The goal is to get everyone’s incentives aligned with those of the patient”

Aside from economic barriers, the sheer quantity of data makes creating a commons a challenging task. According to Tenenbaum, there are 100,000 cancer-related articles published each year, and 10,000 clinical trials at any given time. The standard method of delivery for this information is packed into 5,000 presentations at the annual ASCO meeting. But, “How can anyone absorb all that?” Tenenbaum asks. “It can take another 15 years for the information to diffuse out. Is there a way that instead of taking 15 years this could take 15 weeks? Or even 15 days? There should be no daylight between the clinic and the lab.”

As we learn more about the existing clinical data, Tenenbaum suspects we will find out much of it is wrong.

“This data comes from clinical trials,” Tenenbaum said. “These are the gold standard and they work well when the disease is homogenous, like cardiovascular disease. But with cancer, if you accept the premise that every tumor is unique, then in a randomized trial the patients probably have hundreds of different diseases.”

If a randomized trial shows that a drug helped 50% of the patients, how does someone conclude if that is a worthwhile treatment to pursue? The whole field of personalized medicine is trying to answer just that by coming up with targeted interventions that would eliminate the guesswork. As evidenced by the number of speakers at PMWC, there are lots of ideas about how to do this. Tenenbaum’s vision for creating a commons acknowledges that it will take cross-industry cooperation for all of these ideas to reach their full potential.

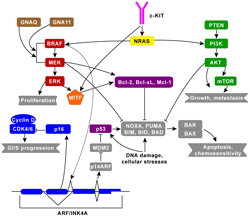

If a patient has run out of standard treatment options, rather than desperately trying things at random, Tenenbaum thinks that patient should have access to the most promising hypothesis for treatment based on the specific genetics of his or her cancer. Cancer Commons is creating Molecular Disease Models (MDM) that enumerate the known molecular subtypes of a cancer. Instead of randomized clinical trials, Tenenbaum sees a shift to virtual trials, which can be run overnight on a small budget, and could compare treatment outcomes for biologically similar patients. There are currently over 900 targeted cancer therapies in the pipeline, which will serve as an arsenal for oncologists to mix and match. Tenenbaum sees cancer becoming a chronic condition, managed with a custom made and constantly evolving cocktail of drugs. The results of each individual experiment are constantly fed back into the MDM, and the standards of care are adjusted.

One of the first steps is to directly enlist patients in getting access to their data and making it available in the commons. While this raises some privacy concerns, Tenenbaum points out that, “Patients are the only ones who have the natural “hair on fire” urgency to do it now… I have not yet met a terminal patient who cares at all about privacy…. here’s my data, help me live.”

Tenenbaum finds the prevailing ethics of data-donation needlessly selfless. “Today when you ask someone to donate something to the cause, there is no expectation that is going to help them. I would much prefer to provide strong personal motivation in the form of ‘the more you tell us, the more we can help you.’” And beyond the patient benefitting, if incentives are aligned, then everyone – molecular and genetic testing labs, pharmaceutical companies, payers, and patient groups – could also gain from sharing data. The next step is to open all the data in the Commons for anyone to build on. Tenenbaum is hoping for some innovative discoveries from the tech community in Silicon Valley, and beyond.

Tenenbaum sees Cancer Commons as a catalyst. “As far as I’m concerned, we have no competitors,” he said. “We are compulsive collaborators. Our goal is to bring as many people as we can to the table. Anyone in this space that would like to join forces to really accelerate the pace of innovation and improve the outcomes for today’s patients, I would welcome them getting in touch with me. There is room at the table, and we need them.”