Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Making Miku

The Pop Star of the Future will be Crowdsourced

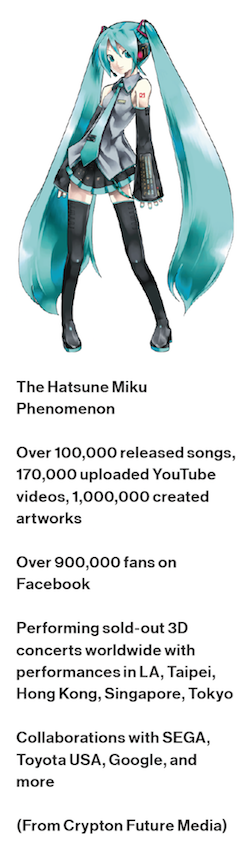

Japanese pop star Hatsune Miku has never written a song; she relies on thousands of songwriters. She’s never chosen an outfit for herself or contributed a single idea to any of her music. In fact, her image is by definition manufactured—because she’s not a human being.

Miku is a cartoon character created to represent a piece of software, a “Vocaloid” computer program that simulates a human singing voice. She only “sings” what she is programmed to sing. Her only public “appearances” are in illustrations and thousands of animated videos on the Internet and, occasionally, at sold-out concerts where she takes the stage in hologram form. And yet, she might be the most “authentic” pop star to ever “live.” That’s because the countless collaborators who create her songs, illustrations, and videos are, with very few exceptions, not commissioned to do so. Most of them are just fans who want to be part of something they love and value.

Miku is a cartoon character created to represent a piece of software, a “Vocaloid” computer program that simulates a human singing voice. She only “sings” what she is programmed to sing. Her only public “appearances” are in illustrations and thousands of animated videos on the Internet and, occasionally, at sold-out concerts where she takes the stage in hologram form. And yet, she might be the most “authentic” pop star to ever “live.” That’s because the countless collaborators who create her songs, illustrations, and videos are, with very few exceptions, not commissioned to do so. Most of them are just fans who want to be part of something they love and value.

“Miku is a character that anyone can use freely to express themselves,” Kazuhiro Sasao, inventor of a keytar- like instrument called the “anogakki,” that can emit Miku’s singing voice, explains in “Mikumentary,” a documentary series about the virtual singer. “She allows people to share their skills with many others.”

Fans, primarily in Japan, but also around the globe, work together to create Miku media.

“Making, remixing, receiving, sharing, debating, customizing, and then recirculating yet again,” says Tara Knight, the film’s director and a noted Miku expert. “For many fans it’s this kind of meaningful participation that’s the real motivator.”

And the way these fans work together, the art they create, and the technology that makes it all possible tells us some important things about the future. From Miku, we can learn how massive collaboration happens, how collective ownership of a character is negotiated, and how a virtual person can embody the aesthetics, intentions, and values of a crowd in a way no human ever could.

A Virtual Star is Born

Hatsune Miku was, at least initially, the creation of a company. In 2007, music software developer Crypton Future Media made a “Vocaloid”—a synthetic voice that can be programmed as a digital instrument and added to a song—and to market it, they created a character to go along with the voice. Crypton came up with the barest of biographies—she’s a 16-year-old pop singer whose name is Hatsune Miku, which means, roughly, “first sound of the future”—and hired a local artist to draw her. Then, they released her into the wild with only some minor restrictions on what fans could do with the character. In a matter of months, the Internet grabbed hold of her and hasn’t let go since.

Not long after the software’s debut, songs using Miku’s voice started popping up on NicoNico Douga, a Japanese video-sharing site similar to YouTube. While the software was initially developed so that a band could just drop her “vocals” into a song the way they’d use an electronic instrument, an online community popped up that was using it in a different way. They were making Miku, the character, their songs’ primary “artist.” They’d write songs from her point of view, as if she was a real person singing about her life. Other fans took the songs and made artwork and videos featuring the character singing and dancing. And many of these songs became so successful on these platforms that many of the artists were able to distribute and sell physical CDs, some selling in the hundreds of thousands.

And it didn’t stop with songs and videos. Fans have developed all kinds of Miku media products and applications—from software that lets you program dance moves for a 3D-rendered Miku to immersive VR experiences that let you share a walk on the beach with the blue-haired idol.

“If you can imagine an activity, there is probably someone building a version with Miku or other Vocaloids,” Knight explains. “And if not, you can start that activity within, and for, a largely supportive community.”

As a result of this massive fan participation, Miku is iconic in Japan today.

The Miku Economy

Creators and companies have always struggled to retain control over their intellectual property and brand image, but the last decades have made tight control nearly impossible. Some have come to see this shift as an opportunity to engage more people and even outsource some creativity to the crowd. But doing this effectively often proves easier said than done. And while many fail in embarrassing ways (think about every fast food chain’s participatory social media campaigns), Miku is proof that you can strike the right balance between control and collaboration. For the vast majority of works created using the character, Crypton doesn’t receive any money. Artists don’t have to pay royalties to use Miku’s voice, even for commercial purposes, as long as they legally obtained the software. And they can use her image for non-commercial purposes without permission from the company. However, Crypton sees plenty of profit from merchandising and endorsement deals.

In Japan at least, this isn’t totally unprecedented. Fan fiction, in the form of fan-made comics, videos, and illustrations, is a huge industry unto itself. There are large conventions dedicated to buying and selling fanworks made with copyrighted characters and settings.

In Japan at least, this isn’t totally unprecedented. Fan fiction, in the form of fan-made comics, videos, and illustrations, is a huge industry unto itself. There are large conventions dedicated to buying and selling fanworks made with copyrighted characters and settings.

“The culture around intellectual property is just different,” Russell Chou, a California-based fan asserts. “[In Japan], they see this kind of fan creativity as an important source of energy. And the creators of some of the most popular original comics and animation today increasingly come from these communities themselves, so they’re more likely to take a really relaxed attitude towards policing the intellectual property that they create.”

Indeed, Crypton has managed to make money without exerting control over what fans do with the character or clamping down on pirating or illegal downloads. Instead, they partner with the likes of SEGA and Toyota to make games, throw concerts, and create ad campaigns.

Miku fandom represents a different creative and commercial ecosystem: Fans create songs, videos, and artwork. The community vets contributions and popularizes what it thinks are the best works. Then Crypton partners with, say, SEGA to create video games using the fan art and videos. When the game is sold (and some of her games have netted record sales), Crypton, SEGA, and the fans whose works are included in the game get compensated.

This economy isn’t without controversy. Some segment of the fandom objects to profiting off Miku works altogether. Zaneeds, a popular band that uses Miku as their vocalist, has refused to license their music for inclusion in games and concerts. But the biggest controversies often aren’t about money at all.

For instance, a Japanese politician once tried to create a Miku song for their campaign—and it tanked horribly due to fan backlash. And when Crypton made a deal with Toyota to use Miku in a campaign to promote the Prius in America, they ended up alienating the community they were hoping to engage. In the campaign artwork, Miku was drawn to look less cute and diminutive, which was interpreted by fans as altering her to reflect “American preferences.” The fan protest was rapid and widespread.

For instance, a Japanese politician once tried to create a Miku song for their campaign—and it tanked horribly due to fan backlash. And when Crypton made a deal with Toyota to use Miku in a campaign to promote the Prius in America, they ended up alienating the community they were hoping to engage. In the campaign artwork, Miku was drawn to look less cute and diminutive, which was interpreted by fans as altering her to reflect “American preferences.” The fan protest was rapid and widespread.

“Generally, this kind of thing wouldn’t be an issue,” Chou opined. “[When fans are doing the creation] no one polices what anyone else does. If you don’t like what someone else is doing with Miku, the community just doesn’t promote it, and then it doesn’t get popular.”

The Crowd, Embodied

Outside of Japan, Miku is best known for her often sold-out hologram concerts. The novelty of massive crowds cheering for a fictional character has earned her an appearance on “The Late Show with David Letterman” and a gig opening for Lady Gaga. But much of the stateside coverage of her focuses on the artificial, highlighting what’s not really there, a human performer, instead of what is, a community.

“Miku became known as a virtual pop star in the West, primarily due to the Western media reporting on the concerts with little prior knowledge of Vocaloids,” anthropologist Lin K. Lei wrote in a 2013 paper. “Internally, these concerts are a form of social gathering, rather than actual concerts. Their crowdsourced nature makes a Vocaloid concert a uniquely different experience from a traditional concert. When these songs are performed on stage, fans feel as if they are celebrating the success of someone they see as being one of them. In this perspective, Miku is not so much a virtual pop star but rather a symbol of the collective efforts that culminated in a concert-style celebration.”

And that’s the true significance of the hologram. The Miku hologram is a symbol of collective efforts and identity given humanoid form. And it suggests a world in which ideas and symbols can walk among us. We’ll be able to talk to them, listen to them, and watch them dance.

“People focus on the pop-star thing, the teenage girl with the blue hair and the short skirt and all that,” says Ian Condry, MIT professor of Japanese cultural studies. “But [Miku] really represents a whole different way of collaborating…and expressing the collective will. And this could have implications for all sorts of things, including politics.”

A politician is meant to represent the will of their constituents. Just as an activist is meant to represent the ideals of their movement. And a pop star is expected, on some level, to reflect the aspirations and identity of their fans.

In many ways, it makes sense to have human symbols for communities or ideas. We know how to interact with human beings. And so having a person act as a symbol for a collective makes it easy for us to engage with that collective. But it’s an imperfect arrangement. The person’s values or priorities may change in such a way that they are out of sync with the collective. And the pressure to continue to meet their obligation to represent the community can be overwhelming and painful for the person. Likewise, if the person is involved in a scandal, it can discredit their entire community.

Japan has a long history of anthropomorphizing abstract concepts and, in general, may be more comfortable interacting with an avatar that represents a collective. But in the future, if a humanoid avatar proves to be the best politician, brand spokesperson, or movement leader, we could see acceptance spread far outside Japan. And if that were to happen, we might look back on Miku, not as a pop-culture phenomenon, but as an ancestor of an entirely new digital species.

FUTURE NOW—When Everything is Media

FUTURE NOW—When Everything is Media

In this second volume of Future Now, IFTF's print magazine, we explore the future of communications. In our research process, we traced historical technology shifts through the present and focused on the question, “what is beyond social media?”

Think of Future Now as a book of provocations; it reflects the curiosity and diversity of futures thinking across IFTF and our network of collaborators. It contains expert interviews, profiles and analyses of what today’s technologies tell us about the next decade, as well as comics and science fiction stories that help us imagine what 2026 (and beyond) might look and feel like.

For More Information

For more information on IFTF's Future 50 Partnership and Tech Futures Lab, contact:

Sean Ness | sness@iftf.org | 650.233.9517