Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Making is a Way of Experiencing

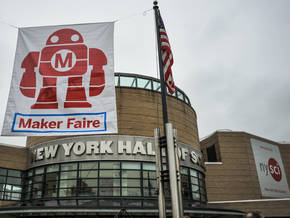

Held at the New York Hall of Science in Queens, the World Maker Faire brought together makers of all ages and creative backgrounds.

I had the opportunity to be at the World Maker Faire for the first day as a social investigator for the Governance Futures Lab. Questions were on my mind, and I was eager to learn from new social inventors and look for trends.

I had the opportunity to be at the World Maker Faire for the first day as a social investigator for the Governance Futures Lab. Questions were on my mind, and I was eager to learn from new social inventors and look for trends.

Upon first entering the park, a man was rocking out on an electric guitar made of a hockey stick, and a 4 year old girl was touching two LED wires into conductive Play-Doh, giggling as it lit up.

"Aloha Lindsea!" called my friend from Hawai'i, Jerry Isledale, US program director of SpaceGAMBIT (Global Alliance of Makers Building Interstellar Technologies), spotting me from the NASA booth.

SpaceGAMBIT is an international network of space enthusiasts that operates through hackerspaces and makerspaces, supporting space-related research and development. Jerry also started the Maui Makerspace, which is a bunch of shipping containers filled with fabrication tools in the middle of a sugar cane field, deep country. Though he lives on a different island than I do, we met at the local Unconference, and again at the Bay Area Maker Faire.

I couldn't talk long, though, Regina Dugan, former DARPA director, was about speak on the Innovation Stage. Her talk was entitled, "The Future Is What We Make It."

In 2012, Dugan left her position as director of DARPA to go into an executive role at Google. She's now senior vice president at Motorola Mobility with big dreams of creating an open hardware system that rivals open source software.

This 21st century Information Age is becoming a time where we're increasingly able to manipulate and tinker with matter, she began.

She shared a project she's working on with Motorola called MAKEwithMOTO—a maker's take on an ad campaign. It's an attempt to create a deeper connection between people and their phones by engaging them through the tools and the freedom to tinker with them.

MAKEwithMOTO is not your typical ad campaign—it was a group of hardware and software hackers that took a road trip across America in a velcro covered mini- and VW bus, stopping in universities and Maker Faires in 9 cities to hold "make-a-thons." In each location, the Motorola smartphone-themed make-a-thons featured the latest 3D printers, laser cutters, and other toys.

It seems like yesterday the DMCA was breathing down the neck of anyone trying to jailbreak their phones, yet now Motorola sees something else in this idea, maybe a little like Radiohead did with In Rainbows. In any case, the corporation seems to be acting on the assumption that consumers actually want less consuming and more making.

Looking out at the audience, Dugan finished her speech hopefully, "One day, the ability to make will be in the hands of all."

Massimo Banzi, took the stage next, the co-founder the Arduino project, an open source electronic platform that allows people to create interactive electronic objects. With the kind of ecosystem Motorola would love for their smartphones, Arduino boasts a vibrant and diverse community of developers and enthusiasts. Many represent at Maker Faire. Banzi emphasized, "Our offices are also Makerspaces and Fab Labs, we work side by side with communities. They're an important part of what we do."

And for the community, Arduino reciprocates—if you make something with the open source hardware platform, they offer to help with crowdsourcing and advertising. "So let's collaborate," finished Banzi.

Leaving the main hall to check out the Giant Mousetrap, I ran into one of the mentors from the Millennial Trains Project, Mike Zuckerman of [freespace]. He was standing in a shipping container wearing slippers, a smile and a Governance Futures Lab t-shirt.

Leaving the main hall to check out the Giant Mousetrap, I ran into one of the mentors from the Millennial Trains Project, Mike Zuckerman of [freespace]. He was standing in a shipping container wearing slippers, a smile and a Governance Futures Lab t-shirt.

The shipping container he's standing in has a blackboard wall for drawing, and a mural of vast Mars-like terrain painted by a local NYC artist. Kids clustered around three humming Cubify 3D printers in the container next door.

A collaboration between [freespace], ekoVillages, and ReAllocate, the team set up the two freight containers covered in etherial outer-space scenes, decorated with abandoned Maker Faire materials, all in three days. The idea is a small example of a larger concept—there are 30 million of these empty metal containers, and they can be rapidly deployed and customized to meet the needs of any community. The modular architecture, explained CEO Adam Hayes, can be used to create a "maker industry", pop up communities for refugee camps, or a modern office space.

Reminded of another modular object, the smartphone Phonebloks, I thought I'd visit the guys behind MAKEwithMOTO again. Weaving through tents overflowing with steam punk costumes, I met Paul Eremenko, who works with advanced technology at Motorola Mobility, in front of the MAKEwithMOTO blue VW van.

I asked Ermenko about what he thought about crowdsourced policy like in Iceland or Finland. Back in his former DARPA days, he introducedcrowdsourced military vehicle design as deputy director of the Tactical Technology Office.

Eremenko responded with system design and complexity. On open source software projects, you can manage complexity with a computer—a compiler can test for any logical errors in code. So even if it's written collaboratively between many people, you can see if it works, Eremenko explained.

He continued, describing how thermal and electromagnetic systems can be compiled and tested. CAD is also useful for modeling physical designs.

But social systems like governance are different. They're at the bleeding edge of complexity. That's why crowdsourcing social systems is a different beast; they're far more complex. There's no compiler to test society for any logical errors. With social system creation, the experience has to be lived--you have to experience to know.

But social systems like governance are different. They're at the bleeding edge of complexity. That's why crowdsourcing social systems is a different beast; they're far more complex. There's no compiler to test society for any logical errors. With social system creation, the experience has to be lived--you have to experience to know.

As we were talking, the Maker Faire bustled behind us. All around, people were modeling new systems, and it was fun. Makers were experimenting with human-matter interaction and systems of many kinds, including the electronic connections the little girl made with an LED and the social connections that emerged from the shipping container painted like Mars. The Faire was conducive to all kinds of tinkering and a place that encouraged the experiencing of systems, whether software, hardware, business, or social.