Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Inventing a Toy in the 21st Century

What do you do when you want to manufacture and sell a toy?

A few years ago I would have told you to start with a prototype, do some patent research, try to get in touch with a manufacturer, and somehow license the idea. This is what I did, or at least tried to do. But that was a few years ago, and now we live in the future! And in this future everyone has the tools to make potentially anything. This is the story of how I tried to bring a toy to market, failed, but then made it anyways, and now I'm letting the internet decide if it is worth manufacturing on a large scale.

Ever since I can remember, I have been fascinated by geometry, so I was the happiest (big) kid in the world when my mom got me a set of small round magnets called Buckyballs. I sat on the floor making geometric shapes for that entire day. Over the next few months I spent countless hours playing with these magnets. Then, while taking a morning shower, I had an idea for a magnetic toy. The idea was to attach one buckyball to each corner of a plastic triangle. There are some magnetic construction toys out there that are similar, but this is toy is unique because it has a magnetic ball floating in a spherical chamber, allowing it to automagically realign the polarity. This was my hunch anyways, so I went and looked online. Sure enough, no one was using this technique.

I started with a prototype made of tape and heavy paper. It didn't have the automagic-aligning spherical chamber, but this proof of concept demonstrated that the magnets were strong enough to form large, stable shapes.

After this, I started my patent research. Having absolutely zero training in patent law, I turned to online tutorials on how the US patent system works. I applied for filer status and printed off stacks of similar patents which had possible overlapping claims with my own invention. I found two toys in particular that had claims, buried deep inside the patents, which were relevant, but not explicitly for the same use. To the best of my abilities I had surmised that mine was indeed a novel idea and at least worthy of a patent application.

Writing up a patent seemed pretty straight forward, look at a bunch of other patents and followed the framework. I drew up some diagrams and started writing my claims tree, but then I ran into a wall. The two relevant claims which I had discovered earlier were contradictory to each other, and these were international patents, which are even trickier than American patents. The patent-writing tutorials I had found weren't specific enough to address this issue. I didn't know any patent attorneys at the time, so I looked one up on Yelp. In retrospect, I should have found someone who specializes in toys, or at least likes toys, because several hundred dollars later, I was right where I had started. I still had no idea how to solve this issue of patenting.

In parallel with writing the patent, I was looking into manufacturing. There was a local company that designed dyes for mass manufacturing injection molded parts. This guy loved the idea, and was very enthusiastic about designing the complicated several-part dye for releasing a widget that has a negative draft angle on it. Unfortunately, the cost for just making the dye had more zeros on the end of it than something I could afford.

This whole process had taken about a month. I had learned a great deal about patent law, manufacturing logistics and a little bit about licensing. Most everyone who heard about the idea (and would be willing to play with a toy), absolutely loved it, but I couldn't make it happen. It was taking a lot of time, and I didn't have the resources. One afternoon I briefly met with a few people who license ideas like this, but it felt sort of like a scam, and I was uncomfortable just signing my intellectual property to someone. So I shelved the project and persued an internship here at the Institute for the Future.

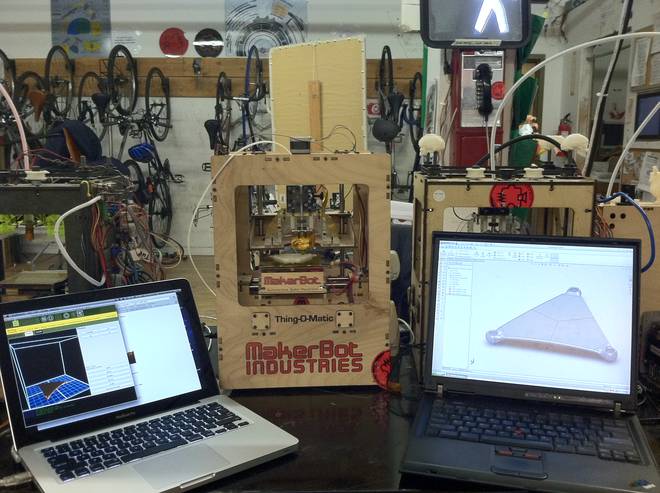

Upon arriving to San Francisco, I was quickly introduced to Nosebridge, a local Hackerspace. In addition to electronics hacking, laser cutters, a darkroom for developing film, a full metalshop with lathes, a CNC and a laser cutter, there were 3D printers. As soon as I saw what they could do, I knew that I needed to print my magnet toy. The original design didn't work very well on the 3D printer, so I rebuilt it in the computer, optimizing the design for this method of manufacturing. After some trial and error, I found the perfect size spherical chamber to fit a buckyball. The toy totally worked, and what more, it was tons of fun to play with!

Due to my frustration with the patent system, I shared the design file on Thingiverse, an online library of 3D objects, so that anyone with a 3D printer and Buckyballs could make their own magnet toys. Lots of people printed their own and shared pictures. Someone even modified the file so that you could print out multiple toys at the same time, and they re-shared it as a derivative. The toy was published under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license. This means that anyone is allowed to make this toy, and even modify it, so long as they attribute their creation to the original creator (myself), and and so long as they do not sell it for commercial purposes. This lets people play with the idea, innovate on it and share it with their friends. Meanwhile, I can be sure that no one steals the idea and starts selling it at the gift shop, but if I want to sell it for my own profit, this is allowed.

For about a year, I was content playing with my new toy, making shapes, and giving them to friends. It felt good knowing that other people liked playing with them, too. Then I started reading Chris Anderson's book, Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. In this book, Anderson writes about how ten years ago, unless you were willing to risk your life savings, your credit, and the well being of yourself and your family, it was nearly impossible for an individual to take a product to market. The big companies simply controlled too much of the supply line and the means of production. Plus these companies could afford a team of lawyers to find a way around inventors trying to make a fair wage or start a company. Anderson further writes that the environment for creating products is different now. Through hackerspaces like Noisebridge, or the makerspaces that are springing up in public libraries, anyone can now prototype their ideas, and that anyone can take their idea to market through services like Quirky.

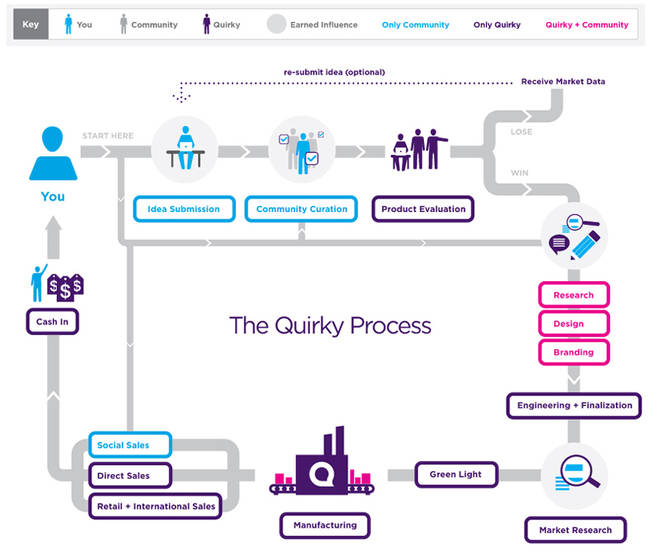

Quirky is a service where anyone can submit an idea, then everyone can vote on whether or not they like it. If enough people like the idea, including Quirky's internal design team, it goes into development. In this phase, both community members and the Quirky team collaborate to improve and refine the idea. After the idea is shipped off for manufacturing, the community can help market the product as well. Everyone who participates in this process — the inventor, the community, and Quirky — share the profit fairly.

I'm not sure if the Quirky community will like this idea, but I'm not really taking a large risk in submitting it. To keep spam down, Quirky charges $10 to submit an idea, and the whole process only took about 20 minutes of my time. This method is drastically different from the month of patent research, attorney fees, and meetings about manufacturing. To speak nothing of the cost for tooling, and the risk of total failure. I am comfortable submitting my idea to Quirky because it is a transparent process, and I am excited to see how others might improve on the idea. And even it it doesn't work, no big deal.

You can follow along with, and even participate in this story on Quirky's website. Let me know what you think.