Future Now

The IFTF Blog

What Social Structures Improve Well-Being?

One of the topics we'll be exploring at our Health Horizons conference this week involves how emerging sharing practices are creating new strategies for improving health and well-being.

Take one of my favorite examples, that my colleague Anna, highlighted last year: The Good Gym. Exercisers sign up for runs in their neighborhood, and in the process, partner with a local senior who they visit and drop off food or medication, or just hang out and talk to, as part of the exercise process. With the Good Gym, the idea is to connect people to share in the process of sticking to exercising--but the concept of the sharing economy is broader that encompasses small scale act, but also includes large scale efforts to share cars and other physical goods. It is, in other words, where instead of owning things, we rely on each other to share things we need, when we need them.

But one question I've been wondering about is if the act of sharing itself is good for well-being. Most of the research I've been able to find seems to focus on how sharing can create new kinds of social capital, at least in the context of social networks. I haven't been able to find much in the way of sharing physical goods, but there's some interesting research examining how sharing information impacts well-being.

Take a recent article by Moira Burke, a computer science grad student and summer intern with Facebook's data team, which examines the ways in which sharing on Facebook relates to subjective well-being. As she describes it, sharing online is linked to improve social well-being in a couple of ways:

We chose common types of surveys measuring two kinds of social capital: 1) "bonding social capital," the emotional support we receive from our closest friends, and 2) "bridging social capital," the new information we get from a diverse set of weaker acquaintances—think of these like a friend-of-a-friend who tells you about a job. We also measured "loneliness," the difference between desired and actual social interactions....

The results were clear: The more people use Facebook, the better they feel. They have higher levels of both kinds of social capital, and feel less lonely. This holds across age, gender, country, romantic relationship status, and even self-esteem and happiness (two additional factors measured in the survey)....

Direct sharing [by sending messages, posting photos, etc.] was linked to better well-being while passive consumption was not. Regardless of how much time people in the study spent on Facebook, how many friends they had, and how many News Feed stories they read, those directly interacting with their friends scored higher levels of well-being.

Notably, in the academic article, Burke points out that passively consuming information--without contributing or sharing with others--actually reduces bridging capital, and increases loneliness. This seems to mirror some findings from public health that find that participating in the world around us improves physical health, as well as psychological and social well-being. In particular, one study has found a particularly strong relationship between high levels of bridging social capital and physical health outcomes.

This is notable, I think, because sharing goods and activities with previous strangers is, at some level, all about creating and enhancing bridging social capital--which is to say, enabling participation, developing weak relationships, and enhancing connections between people where none previously existed. My guess would be that sharing physical goods and activities would produce far more bridging capital than online interactions alone.

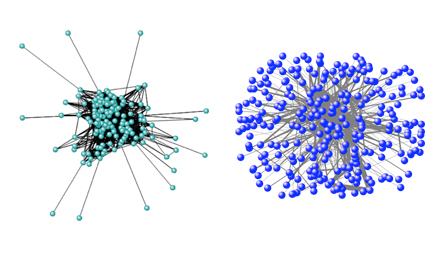

It also contrasts with a separate, recent study of social networks and crime, covered in Science News that wasn't about social capital or well-being, per se, but sheds some light on what sorts of networks don't share. The study used network analysis to examine email patterns from Enron and found that. when pursuing real initiatives, emails and information were exchanged robustly, whereas when pursuing illegal activities, people tended not to share. The image, and quote below, come from Science News:

Aven’s analysis compared communications regarding three legitimate innovative projects and three corrupt ones that went by the names JEDI, Chewco and Talon. Communications regarding the shady deals took on a wheel-and-spoke shape, a setup that maximizes secrecy and control. A small, relatively informed clique occupies the hub at the center, communicating with protruding spokes that don’t share ties with each other. The hub gets information from the spokes, which in their isolation are less likely to whistle-blow and can be played off each other.

Now, these studies are all sort of anecdotal - they're studies of information sharing, not sharing physical goods, and the latter study of Enron's networks seems to have a certain sort of obviousness to it. (Of course criminal networks are intentionally small and hierarchical.) But together, I think they point toward a new way that we'll understand health and well-being in the coming decade--where participatory networks with lot of free exchange come to be seen as key markers of well-being.