Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Podcast: Beyond Wearables - Get Ready for Broadcast Hugs and Books that Punch You in the Stomach

A discussion with Miriam Lueck Avery, research director at IFTF for the New Body Language research.

Beyond Wearables: Get Ready for Broadcast Hugs and Books that Punch You in the Stomach

For a decade, we’ve been talking about a future where we’ll have computers on our wrists, in our eyeglasses, even implanted under our skin. Today, that future is here. From gold-plated Apple Watches to the much-mocked Google Glass to vibrating fitness tracking wristbands available for $30 a piece in a 3-pack at Costco, wearables have gone mainstream. We now have the technology to put computer power and Internet-connectivity pretty much anywhere in, on or around our bodies. And it’s clear that, in a decade, this technology will become exponentially more powerful and accessible. But what’s less clear, is why we would want these body area networks, how we’d arrange and configure them and what we’d use them for.

For a decade, we’ve been talking about a future where we’ll have computers on our wrists, in our eyeglasses, even implanted under our skin. Today, that future is here. From gold-plated Apple Watches to the much-mocked Google Glass to vibrating fitness tracking wristbands available for $30 a piece in a 3-pack at Costco, wearables have gone mainstream. We now have the technology to put computer power and Internet-connectivity pretty much anywhere in, on or around our bodies. And it’s clear that, in a decade, this technology will become exponentially more powerful and accessible. But what’s less clear, is why we would want these body area networks, how we’d arrange and configure them and what we’d use them for.

As part of our 2015 Technology Horizons research into Human+Machine Symbiosis, (the evolving relationship between humans and machines), we set out to answer this question. And the answer we found is the “New Body Language,” an exploration of how technology in, on and around our bodies will help us express ourselves, connect our communities, alter our anatomies, and help us fulfill our longstanding and deeply human intentions and aspirations. We’re pleased to make this body of research public for the first time in the inaugural issue of Future Now, IFTF's new print magazine.

In this episode of IFTF's podcast, Mark Frauenfelder sat down with Miriam Lueck Avery, who led the New Body Language research, to discuss how wearables, implantables, and wireless networks will connect our communities and alter our anatomies in the coming decades.

Subscribe to the IFTF podcast on iTunes | RSS | Soundcloud | Download MP3

TRANSCRIPT:

What is the New Body Language?

This research started as a question: what's beyond wearables? We wanted to find out how the technologies that are inside our bodies, on them, and around them will change human identity and culture. "New body language" is metaphor for these new technologies, combined with the body language of gestures, stances, poses, expressions, and how they resonate with different cultural archetypes and human intentions.

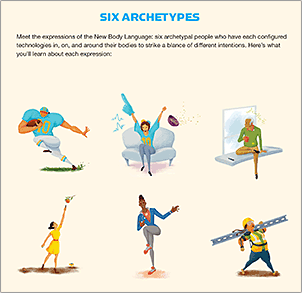

Tell me about the six different archetypes you developed to explore expressions of the new body language.

Each of these archetypes helps us learn something about different kinds of expressions. These six were never meant to be a complete and total list, but as generative provocations. Some of them, like The Athlete, are part of a pair, so The Athlete and The Fan speak to each other, both conceptually but also literally, through their devices.

Each of these archetypes helps us learn something about different kinds of expressions. These six were never meant to be a complete and total list, but as generative provocations. Some of them, like The Athlete, are part of a pair, so The Athlete and The Fan speak to each other, both conceptually but also literally, through their devices.

The Athlete archetype was inspired by the high-end, sophisticated wearables happening in professional sports, used to monitor, train and extend the capacities of these really selective, highly paid, highly rewarded individuals who spend large parts of their lives getting really, really good at a few specific things and performing those with amazing skill. All of these wearable monitors that we're tracking, the movements of muscle groups or the impact of a collision for football and rugby players – on one hand that data is being used simply for gambling. It's used to make bets, both literal personal bets and also financial and sponsorship bets on the performance of particular people. On the other hand, the data is being used in interesting ways to convey the experience of the athlete to the fan.

A real world example is the Alert Shirt. It's a project that used a jersey that rugby players would wear paired with a jersey that rugby fans would wear. The player's shirts had heat, compression, impact sensors in them. The sensors were wirelessly connected to fan's shirts, which had actuators in them, to give fans a visceral sense of what playing a contact sport like rugby actually felt like.

So this paired archetype was about playing with and totally messing up the notion of a spectator sport, where your body could participate in this experience; where anybody's body could participate in the experience of professional athletes.

There are parts of our bodies that we're used to communicating with: voice, body language, facial expressions. This new body language is about communicating using parts of our bodies that never had a voice before. Things like perspiration, heartbeat, brain state, and stuff like that.

It's exciting to think about how some of these levers that are not auditory, not visual, not the usual medians that we think about for communication, are much more visceral and emotional. For example, capillary dilation, body heat, and diaphragm compression are some of the best triggers that we know of to create emotional states. One of my other favorite signals that informed, both The Athlete and The Fan archetypes, is Sensory Fiction, which is an MIT Media Lab project. It was a book that you would read, and it came with a harness that would actually compress your diaphragm or make you feel a weight on your shoulders or a lifting of a weight on your shoulders, and light and sound and vibration. That all worked together to create a much more immersive story than could be told otherwise.

It reminds me of something psychologist William James said: "We are afraid because we run, not the other way round." In other words, doing something to your body like that can create an emotional response.

Action and emotion don't just have a motivating or a corollary relationship, but they actually reinforce each other. The other thing about the relationship between The Athlete and The Fan, besides different parts of our bodies being part of that communication, is that the scale of communication is different when we start engaging those parts of our bodies. For instance, you might think of a hug as something that is totally intimate. It can only happen between a handful of people at most, but with this kind of technology you can think about hugs that can actually be delivered to millions of people, hugs that could be broadcast. That shift in what we think of as mass media and what we think of as intimate and a personal communication is fascinating and cuts in many, many directions.

Tell me about The Eater and The Unwell as an archetype pair.

The Eater is young, and is based on IFTF's research into the future of food and the future of personal well-being. We're seeing children and young people becoming much more engaged in their own bodies. The Eater is the avatar of the young food movement. She allows us to think about what these technologies look like in the hands of youthful curiosity, and a fascination with and a sense of wonder about the world, and a generation for whom the Quantified Self movement has always existed. The idea that she would be interested in the contents of her food and the contents of her guts and her microbiome and the contents of the soil, and how all of those things interact is a futuristic story, but we see current signals from things like uBiome and the American Gut Project and all the citizen science that's happening in microbiome science, where high school classrooms are sending in samples of their poop and contributing that data to science.

The Eater is using this new body language technology to stay healthy and improve her health. The Unwell archetype seems to be someone who is using technology to compensate for the loss of ability, like an artificial intelligence to help fading memory, and a camera that records smells because smell is associated with memory. How did you identify The Unwell as an illustrative example of new body language?

A lot of our research in health care looks at demographic and epidemiological trends. We've been very interested in aging in general, but in particular this wave of dementia and Alzheimer's and other cognitive impairments, because that's going to be a huge issue in the next 10 to 20 years, and our social relationships, our legal practices, our care systems are not well prepared for that reality. The Unwell takes the assumption in the next 10 years we’ll come up with responses to that, but a lot of it is still on families and the individual. The Unwell is our avatar of the slightly tech-savvy person who's recognizing that they're in a state of cognitive decline and grasping for anything to help them cope with the loss of their capacities, to supplement their capacities, and to live the kind of life they want to life as much as they're able, but also interact with their family in a different way than caregivers today are able to.

There are lots of inspiring projects around memory-mapping for people with Alzheimer's. They can document memories so they can be re-experienced. Some of those are through VR, some are through wearables like the Narrative Clip (no longer in production). There's a powerful story in how we express our body language as an expression of family, when we want to share things with our families, when we want to hide things from our families. The Unwell helps us explore when you want to be connected to others and and when is it appropriate or empowering to be isolated from others.

The final two archetypes are The Partier and The Laborer. Is that about working hard and playing hard?

One of the things that I love about The Partier and The Laborer is that The Partier is actually working by playing and The Laborer is playing while she works. There's been this erosion of the line between what is a working technology and what is a playing technology, and both of these archetypes help us think about that. The Partier specifically, he's not just a person who is partying. His life is partying. He gets his income from partying. He is a sponsoring partying personality. All of these technologies he’s wearing help him monetize his skill of having a good time, and to share, amplify, and use it to influence other people's experiences. He has a bio-reactive DJ bracelet that uses his body's feedback to change the music in a club. His clothing changes with his moods. He monetizes his experiences in the same way Instagram and YouTube personalities do today.

Probably the most controversial thing on here is the biometric party tracker that broadcasts his blood alcohol level and becomes a game for everyone in the club. "Can you keep up?" There's a lot of interesting questions here about party culture, about safety and the ethics of promoting a partying lifestyle, which has come up in conversations that we've had with our clients in the food and beverage space.

How about The Laborer?

We wanted to get as far away from that white collar guy in a business suit as we possibly could, so we were looking at skilled manufacturing jobs and thinking about how people with differing physical capacities could continue to do laboring jobs in the future with these technologies. The foundation of The Laborer is an exoskeleton that amplifies her physical capacities and an augmented reality headset that helps her interact with potentially dangerous work sites in a safe, and also creepily surveilled, way. These things have some trade-offs.

And, now that people are used to blending their personal technology and their professional technology, might you see that extending out into this kind of world as well? Is the headset she’s wearing restricted to displaying safety and work-related information, or can she take a break and listen to her music without changing her headset? Her friend unlocked the device so now she can, stream stand-up comedy when she takes a break. We're imagining a world where even if something is made for an industrial application, people will still find ways to do the equivalent of playing games on your work phone.

Where do you see all this wearable technology heading?

Let’s follow the path. Back in the 1990s. Thomas Zimmermann at Xerox Parc (who coined the term “personal area networks”) was looking at the computer mouse and thought “all this does is move a point around a display, but there are so many things we do with our hands to gesture, to express, to communicate. Wouldn't it be lovely if computers could understand that language?” He created the first virtual reality handset — the DataGlove — and his work is the source, both conceptually and literally — for gesture recognition and kiosks and things like that today.

There's a bright line between the DataGlove and, say, Google's Project Soli, which is a small chip that can be embedded in anything and basically makes a gesture recognition interface out of it. I think the big takeaway here is that humans gesture. Every culture has a language of gestures.

This is where we can see the body language becoming a computer language and vice versa, Visual and the auditory recognition are about making computers useful without humans having to change their natural behavior.

People and animals have evolved to communicate in certain ways. This technology is changing the types of communication and changing the bandwidth of the signals coming through. How do you think that we're going to adapt to this? Is it going to overload us or is the human nervous system adaptable enough that it's going to be able to accept and interpret and manage all of this new information?

I'm not a neuroscientist, but I give the human nervous system a lot of credit for being quite adaptable. I am an anthropologist, and so I think some people will adopt particular kinds of technologies and other will reject them at different times in their lives, because they do or don't support a particular cultural pattern, even if that pattern is the novelty of adopting something new. That's a cultural pattern that we see in Silicon Valley among people of many national origins.

If these technologies can help us express our individual and our cultural imperatives, we'll go through a lot of discomfort to figure out how to get that value out of them. We've seen that with all of the technologies that have been invented in the last 200 years, and even with earlier technologies like ropes and wheels and fire. None of these are easy things. Even making stone tools requires us to think about space and think about matter a little bit differently than we would have before then. Painting pictures of ourselves gets us to think about our own image in different ways than we would have before then. You can go back 45,000 years to the first pictograms of human faces that the Aboriginal Australians made and imagine that change of the first person who saw themselves in a rock and having that profound mirror experience with something that wasn't alive.

Culturally, we're on the verge of that same kind of phase shift in what we think is alive, what we think has its own sense of expression, how we're able to express ourselves as humans, and how we will use these technologies when they're helpful and ignore or destroy them when they’re not.

This podcast is crossposted on Boing Boing and Medium.

FUTURE NOW—The Complete New Body Language Research Collection

FUTURE NOW—The Complete New Body Language Research Collection

The New Body Language research is collected in its entirety in our inaugural issue of Future Now, IFTF’s new print magazine.

Most pieces in this issue focus on the human side of Human+Machine Symbiosis—how body area networks will augment the intentions and expressions that play out in our everyday lives. Some pieces illuminate the subtle, even invisible technologies that broker our outrageous level of connection—the machines that feed off our passively generated data and varying motivations. Together, they create a portrait of how and why we’ll express ourselves with this new body language in the next decade.

For More Information

For more information on the Tech Futures Lab and our research, contact:

Sean Ness | sness@iftf.org | 650.233.9517