Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Simulacra and Simulations

When video forgeries of human beings roam free

Written by IFTF Distinguished Fellow Jamais Cascio for volume three of Future Now,

IFTF's print magazine powered by our Future 50 Partnership.

Imagine taking a video stream of someone—Vladimir Putin, for example, or Lady Gaga, or your spouse—and changing what they say onscreen to whatever you want to show them saying, with their own voice and face. What would you have them say? What could you do with this as a tool?

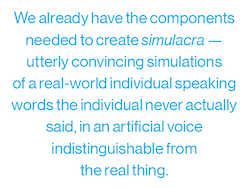

The technologies to make this a reality are coming together rapidly. The startup, Lyrebird, recently unveiled software that can digitally reproduce anyone’s voice from just a one-minute sample. At the same time, a group of students at Stanford created a program called “Face2Face” that allows you to take an existing stream of video of a person speaking and, in real time, reshape their mouth and facial movements to make it look like they are saying a completely different set of words. In essence, we already have the components needed to create simulacra—utterly convincing simulations of a real-world individual speaking words the individual never actually said, in an artificial voice indistinguishable from the real thing. And this is only the beginning. Over the next decade, we can expect two more breakthroughs: Computer graphics imagery (CGI) that has finally passed through the “Uncanny Valley”; and the cost-power curve putting the ability to create believable simulacra in the hands not only of Hollywood special effects artists, but also teenagers with moderately-advanced mobile devices.

The technologies to make this a reality are coming together rapidly. The startup, Lyrebird, recently unveiled software that can digitally reproduce anyone’s voice from just a one-minute sample. At the same time, a group of students at Stanford created a program called “Face2Face” that allows you to take an existing stream of video of a person speaking and, in real time, reshape their mouth and facial movements to make it look like they are saying a completely different set of words. In essence, we already have the components needed to create simulacra—utterly convincing simulations of a real-world individual speaking words the individual never actually said, in an artificial voice indistinguishable from the real thing. And this is only the beginning. Over the next decade, we can expect two more breakthroughs: Computer graphics imagery (CGI) that has finally passed through the “Uncanny Valley”; and the cost-power curve putting the ability to create believable simulacra in the hands not only of Hollywood special effects artists, but also teenagers with moderately-advanced mobile devices.

At their most basic, simulacra technologies offer the combination of a familiar (or at least positively identifiable) person speaking words or behaving in ways that the individual did not actually say or do. The familiarity is critical—the power of a simulacrum comes from connecting a trusted person to words or deeds that are not their own. You aren’t simply seeing a fabricated character, you’re watching a powerful politician, a popular performer, or a beloved relative.

The more worrisome implications of this array of technologies are easy to imagine. Convincing simulations of real people can be shown doing or saying anything, and these tools could be used for creating fake recordings of misbehavior, sowing widespread political confusion, committing various forms of fraud, and much more. In a world where the definition of consensus reality has become increasingly blurry, simulacra could serve as a weapon of mass destruction of trust.

The nefarious uses of simulacrum technology are so obvious and dire, it’s easy to wonder why the biggest breakthroughs are coming from seemingly well-intentioned computer science labs. But a closer look reveals this technology as an array of positive, or at least not outwardly sinister, ways the technology could be used.

We can think of a simulacrum as a filtered version of an actual person, taking an input video stream and changing it to make it convincingly appear to do or be something other than the actual video. A simple parallel would be autotune software that takes a singer’s voice and corrects it (usually quite convincingly), even in real-time. As with auto-tune, the result would be something that’s superficially false but truer to the intent of the user. It’s a form of idealization of both speakers and their words.

In the Internet of Actions (IoA), this most fundamentally manifests as a means of altering perception, especially in visual communication. We could see a version of Skype, for example, that makes users appear more presentable, their voices richer, and that edits their spoken word on the fly to fix mispronunciations and smooth out vocal tics. A video recording of a speaker could be edited further to correct mistakes made while speaking off-script, without requiring the speaker to re-record segments (in filmmaking, this later re-recording is a common process, known as ADR—additional dialog recording).

But this is more than simply making someone look and sound their best on Skype or YouTube. A subtle but important aspect of simulacra technologies is that they will be language-agnostic, meaning that an individual could be simulated as speaking in any language. It should soon be possible to take a previously recorded talk and translate what has been said to a new language, using the speaker’s own voice. This is more than just dubbing: simulacra systems will be able to alter the appearance of the speaker’s mouth to map correctly to the new language, thereby improving the immersive quality of the altered video. As real-time computer translation improves, we will see translation systems in video communication that will do all of this, as well.

Such internationalization technologies will be particularly appealing to film producers, who have come to rely upon global markets to maintain movie profits. Rather than using subtitles (widely disliked by casual movie audiences), or obvious dubbing with local voices, blockbuster movies will show the original actors speaking lines in every market’s language, using the actors’ own voices. (This same technique would also allow for the release of language-censored movies that need not rely upon awkward phrasing to match the actor’s mouth movements—notoriously exemplified by Samuel L. Jackson’s “I want these monkey-fighting snakes off this Monday to Friday plane!” in the television version of “Snakes on a Plane.”)

Hollywood will eventually make even greater use of simulacra technologies beyond censorship and internationalization, as CGI technologies move beyond the Uncanny Valley. Producers—and talent agents—have already started to plan for the ability to show a much-younger version of an actor, or a now-deceased performer, speaking new dialogue in entirely new settings. Such technologies live in the heart of the Animating Objects and Environments strategy of the Internet of Action.

Laws and regulations have already begun to form up around these kinds of technologies. It’s now common for actors and other entertainers to include “post-mortem publicity rights” in contract, even as they have their bodies and faces scanned for easy and detailed 3D simulation. Such restrictions need not be limited to the entertainment world. In 1984, California passed a law guaranteeing “post-mortem publicity rights” for 50 years (later extended to 70) for performers living and working in that state. Such a law could be extended to cover everyone, even non-actors, as simulacra technology becomes more prevalent in the everyday world.

In time, simulacra technologies would go beyond the straightforward recomposition of video. We could combine a visual of the now deceased individual with a vocalization of their written words in order to create post-mortem testimonial simulacra, for example. These might become a recognized way of passing along wisdom or messages from the dearly-departed. A goodbye message from a grandparent could, for example, translate a letter into a video of that grandparent shown to be speaking those words, or connect the message not to a video of the person lying in a hospital bed, but to an old film or video of that individual in their much younger days. Similarly, a late business or political leader could be shown speaking the words of their books, essays, even tweets. Strictly speaking, these would just be “platform shifting” the words, functionally little different from a straightforward video recording of the person reading the messages while they still lived.

In time, simulacra technologies would go beyond the straightforward recomposition of video. We could combine a visual of the now deceased individual with a vocalization of their written words in order to create post-mortem testimonial simulacra, for example. These might become a recognized way of passing along wisdom or messages from the dearly-departed. A goodbye message from a grandparent could, for example, translate a letter into a video of that grandparent shown to be speaking those words, or connect the message not to a video of the person lying in a hospital bed, but to an old film or video of that individual in their much younger days. Similarly, a late business or political leader could be shown speaking the words of their books, essays, even tweets. Strictly speaking, these would just be “platform shifting” the words, functionally little different from a straightforward video recording of the person reading the messages while they still lived.

Adding a level of machine intelligence could allow for more interactive versions of these testimonial simulacra, a way of encoding human activity, and then remixing or modifying the original at will. These more advanced simulacra would be able to answer questions and make observations, at least within the confines of what their originals had said or written in the past. A late family matriarch might be able to give advice about squabbles between siblings, or the founder of a business could be brought in to offer observations about critical deals. At minimum, these simulacra would be pulling ideas and phrasing from existing material closely connected to the issues at hand; as machine learning systems further develop, they may be able to extrapolate how an individual would respond to a new problem.

Of course, there’s no reason why the use of these kinds of techniques would be limited to the dead. Interactive versions of oneself could be of great value to many still quite living people. We could think of this as “multifacing,” a simultaneous, real-time presence in multiple video platforms. A simulacrum on screen would respond with the voice and mannerisms of the user, who could slip in and out of each virtual presence as needed. Users might respond via text-to-speech to “multiface” more efficiently, or may rely on trusted assistants to answer for them. As machine intelligence improves, those assistants would become software agents.

This same set-up could be a powerful part of gaming and game design, as well. In 2015, Bethesda Softworks’ Fallout 4 notably recorded over 13,000 lines of dialogue for the main character, along with 85,000 more lines for various non-player characters. Each line had to be read by a real voice actor; as a result, many players complained that the options for decision-making in Fallout 4 were too limited, as they were constrained by how much time and money could be spent on coming up with and recording various player and non-player responses. Simulacra technology would eliminate that problem, making it simple to turn a script into vocal performance, along with convincing accompanying mouth movement and even visual representation of the famous performers often hired to provide the voices and voice samples.

Simulacra technologies have the potential to give face and voice to virtual representations of ourselves, whether in performances, in work, or in tribute. Even if some people may use these tools for criminal or problematic ends, the economic and cultural benefits of the widespread employment of the technology stands to be profound.

FUTURE NOW—Reconfiguring Reality

FUTURE NOW—Reconfiguring Reality

This third volume of Future Now, IFTF's print magazine powered by our Future 50 Partnership, is a maker's guide to the Internet of Actions. Use this issue with its companion map and card game to anticipate possibilities, create opportunities, ward off challenges, and begin acting to reconfigure reality today.

About IFTF's Future 50 Partnership

Every successful strategy begins with an insight about the future and every organization needs the capacity to anticipate the future. The Future 50 is a side-by-side relationship with Institute for the Future: a partnership focused on strategic foresight on a ten-year time horizon. With 50 years of futures research in society, technology, health, the economy, and the environment, we have the perspectives, signals, and tools to make sense of the emerging future.

For More Information

For more information on IFTF's Future 50 Partnership and Tech Futures Lab, contact:

Sean Ness | sness@iftf.org | 650.233.9517