Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Science Hack Day SF

I went to the Science Hack Day not knowing what to expect. This is the second year that Ariel Waldman – a fellow researcher at IFTF – has put this event together. Since then it has gone international with Science Hack Days springing up in far away lands like Nairobi, Cape Town and Cleveland. This year the Bay Area event was hosted at Brightworks, a maker school located in the heart of sunny San Francisco. About 150 people signed up for the event, with skills ranging from programming and finance to art and engineering. A few people had posted ideas for project directions on a community Wiki, but no teams had completely formed—I don't think anyone really knew for sure what was going to happen. You can never really be sure what you're going to get with a whole room full of talented people who think the best way to have fun over the weekend is to get together for a nerd party and build cool stuff… with Science!

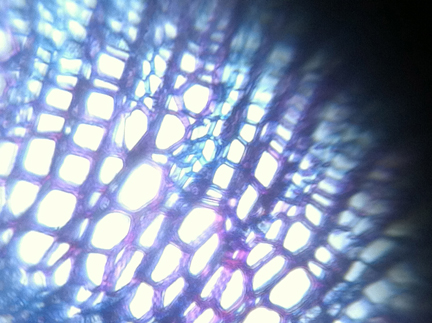

I have recently been slightly obsessed with microscope attachments for the iPhone. This has been inspired by a group of researchers at Berkeley who are building Cellscope which is an iPhone based microscope, and another group of researchers at UC Davis who just published a paper on using a $25 ball lens, an iPhone, and some tape to build a microscope that is "good enough." I had just received a large package containing a 1mm ball lens, which does in fact produce amazing results when scotch taped to an iPhone camera. In the first 30 minutes of Science Hack Day I met Simon who builds his own microscope lenses, and he shared information on how I could—with just a few tools—manufacture my very own microscope lens. Moments later I met Nancy with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (terrifying agency name, very cool person). We had a conversation about the benefits of using cellphone-based microscopes for medical analysis of disease in developing countries, and the potential of using data tracking to stop pandemics. Then a bell rang and it was time for a round of lightning talks where people very quickly explained ideas they were working on.

I went to a talk about Citizen Science where I met Bonnie who wanted to make a centrifuge that she had seen on Thingiverse. The centrifuge is intended to hold test tubes that can be attached to a Dremel. I just happened to have brought with me a MakerBot which is a 3D printer that is capable of printing practically any 3D object you can think of. It had been acting up a bit lately, so it took several tries to print the Dremelfuge, but eventually we got a print that was workable. Unfortunately, both the dremmel and the electric drill that we had at the time didn't spin fast enough to separate the DNA, so she had to go with a hot-cold process (which I still don't quite understand). But manufacturing technologies like MakerBot present new opportunities to (citizen) scientists, who previously might not have had access to the right tools. The next generation of kids are growing up in a world where everybody has access to the tools to modify, create and experiment with anything.

Later that night, while I had stepped out for a quick bite to eat, my sister called. She had gotten involved in building a globe which tracks where the International Space Station is in relation to the surface of the earth. She said they needed a set of gears with a 2:1 ratio in order to finish the project. Now one of the constraints of Science Hack Day is that the doors lock at 10pm and the hackers have to work with the materials they have. My sister called at about 9:45. You can find a lot of stuff in the Mission district at 9:45 on a Saturday night, but tracking down a specific set of gears and getting back to the Hack Day in 15 minutes would be a bit tricky. But I had a solution: we could print the gears. Upon returning to Brightworks, I did a quick search for "gears" on Thingiverse and quickly found a 2:1 herringbone gear that would do the trick. I downloaded the file and modified it slightly. The printer was still acting up and caught fire just a little bit, so printing took a few tries, but hey, that is science. Once we got the gear printed out it was about 2am. Lots of teams were still hacking away, but I was exhausted so I lay down on the floor with my space-themed blanket alongside many other slumbering hackers.

The next day, we put the fixed the gear on the globe, and after some calibration it was good to go. The laser perfectly tracked where the ISS was in relation to the surface of the earth. And finally, I was able to identify the problem with the MakerBot with some help from Glenn on the ISS globe team. After borrowing some materials from a fellow hacker, who was working on an earthquake detection system, I soldered together a quick fix that totally worked.

Next up were presentations by each of the 25 teams who had submitted a project. Such a variety of great ideas! One team built a face mask that mixes the sense of touch with the sense of sight. Another team made visualizations for the Large Hadron Collider, while another team wrote software for a computer microscope beard detector that could sense the presence and intensity of a beard. You can check out the documentation for all of the projects on the Science Hack Day Wiki. Overall, Science Hack Day totally rocked! I met lots of interesting people with an amazingly diverse set of skills and we got to collaborate and build cool stuff and I cant wait for Science Hack Day to happen again next year.