Future Now

The IFTF Blog

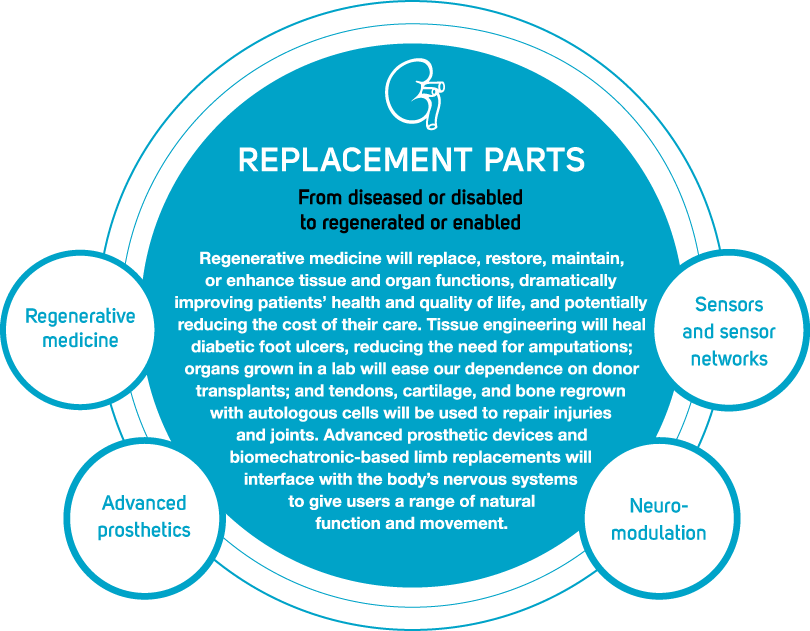

Replacement parts: “We can rebuild him, we have the technology”

Regenerative medicine will replace, restore, maintain, or enhance tissue and organ functions, dramatically improving patients’ health and quality of life, and potentially reducing the cost of their care. Tissue engineering will heal diabetic foot ulcers, reducing the need for amputations; organs grown in a lab will ease our dependence on donor transplants; and tendons, cartilage, and bone regrown with autologous cells will be used to repair injuries and joints. Advanced prosthetic devices and biomechatronic-based limb replacements will interface with the body’s nervous systems to give users a range of natural function and movement.

When we first presented this forecast at a conference, our colleague Vivian told a story that illustrates the potential, and some possible pitfalls, of the growing capacities of regenerative medicine. It was part of a complicated dance of vignettes and exposition with Vivian, Bradley and myself that will remain one of my fondest memories of working here.

Of course, when you get sick enough, you end up having to go to the doctor for help.

That's what finally happened with Eric, who has Type 2 Diabetes. He is a very successful 56 year old lawyer. He has a history of working too much and not taking very good care of himself. He was overweight, ate poorly, and didn’t track his blood sugar levels consistently. As a result, he has had some serious complications from his illness. Last year, he developed a foot ulcer that just wouldn’t heal. The doctors had to amputate his foot. His eyesight also deteriorated because of damage to his retina. And his doctors have been warning him that he may need to go on dialysis. Eric's body is failing him.

Remember that TV show in the '70's? The Six Million Dollar Man? Do you remember the show's tagline? "We can rebuild him. We have the technology."

That was science fiction then. But today, in 2020, we can rebuild Eric. We have the technology. We can replace his failing body parts. And fortunately, Eric can afford the most cutting-edge medical treatments available.

Thanks to research funded over the past decade by the U.S. Department of Defense, Eric received a prosthetic foot that mimics the way a real ankle and foot move. It's called an active prosthetic and it has a small motor that helps power and change his gait. He can walk uphill, go up stairs, and even run. It also has embedded sensors that connect to electrodes attached to nerves in his leg. This provides him with feedback about where his new foot is in space, and helps transmit commands from the nerves to the prosthetic.

Eric also got a different kind of prosthetic—a neuroprosthetic—to take care of his diabetic retinopathy. He had an artificial retina implanted in his eye. (You could think of this as a visual cousin of Michael Chorost’s cochlear implant). It is a microchip that has hundreds of electrodes on it. Eric has to wear a pair of glasses with a tiny video camera mounted on them. It captures images, converts them to electrical impulses, and transmits them to the retinal chip. These electrical impulses stimulate his brain to perceive patterns of light, which has allowed him to see again.

Eric’s diabetes has obviously taken a toll on his body. He is really worried that his kidneys are going to start to fail soon, and that he will need to go on dialysis. He knows that it may be hard for him to get a new kidney, because there still aren't enough donors to meet the needs of all the people on the national registry list. But he has heard about new developments in regenerative medicine, and he is hopeful that if his kidneys do shut down, he may be eligible for a clinical trial. Researchers would use his own cells to grow a kidney in the lab and transplant it in him.

Eric still has diabetes. But now he has a new lease on life, thanks to his new foot and retina.

There’s something incredibly hopeful about this story, and at the same time quite troubling. What if it wasn’t a workaholic with diabetes, but instead a smoker? Another colleague has a friend in his 30s who keeps smoking on the premise that by the time it’s an issue for his body, we’ll have cancer prevention treatments and the ability to regrow whole lungs. We’ll have the technology, but will being able to afford it really be the criteria for who gets to use it? And will the capacities to remedy even late-stage complications to chronic diseases upstage the critical global tasks of preventing chronic illnesses and their most damaging consequences?

There are also questions of these technologies crossing the threshold between treatment and augmentation. I won’t get into that here, but rest assured we’ve written extensively about it in the past and will continue to do so in the future.