Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Recipe Networks and Combinatorial Cuisine

The field of network science continues to find new data sets for exploring technology, economics, biological systems, and social relationships. Two recent articles use recipe ingredients and foods from different cuisines to demonstrate how the lens of network science can create analytics to provide us with new insights into how we eat and what gets eaten.

As industrial food systems offer more homogeneous mixture to people worldwide, a positive implication of these new analytical approaches is that they expand our view of rare possibilities that may be valuable for reaching new food plateaus. These networks map the kinds of combinations of ingredients we eat, and they may help us create and redefine new food cultures with profound cuisines that match regional tastes, transport systems, and changing agricultural capacities.

Recipe Recommendation Using Ingredient Networks by Chun-Yuen Teng, Yu-Ru Lin, and Lada A. Adamic points to how cultural affiliations and regional preferences influence ingredient substitutions among the recipes that people share online. They look at relationships between ingredients and which ones can be swapped out for others. In their discussion they remark that if one included the many available cooking methods, it's easy to see how many new combinations are possible in the recipes we use. In an accompanying blog post, co-author Lada Adamic points out that this kind of understanding of ingredients can be used to predict the success of a new recipe. Recipe networks suggest a precise and intuitive method for combinatorial innovation, and it's another way to create different alternative futures that are firmly rooted in the trials and tribulations of everyday life.

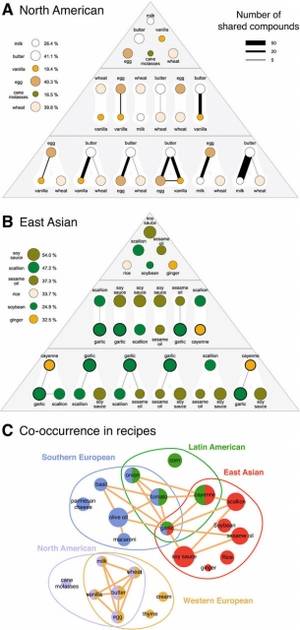

Ahn, Ahnert, Bagrowm and Barabási conduct a similar analysis in their article on the Flavor Network and the Principles of Food Pairing. The authors take a slightly different approach, seeking to isolate what makes unique ethnic cuisines authentic, in order to get at the root of what makes taste and flavor successful. In the flavor They identify "keystone" ingredients that hold together and bridge different ethnic cuisines, like garlic, and show how some ingredients are more prevalent than others. The whole endeavor starts to look very much like a diversity index for different ethnic cuisines. Different cuisines do have different "authentic" ingredients, and they turn out to be ones that are only prevalent in that specific cuisine. One part of authenticity is that some ingredients are "founders" for a given cuisine. These are ones that have been used in the same geographic region for thousands of years and have come to define the cuisine. The authors describe how recipes change over time and discuss how the addition and substitution of higher "fitness" ingredients increases the value of recipes. A ready example comes from the recent additions of tomatoes, peppers, and potatoes to European and Asian cuisine.

Sometimes, even small substitutions and changes in a recipe can affect other areas of life in ways we don't anticipate. Creating forecasts for the future around a recipe allows us to ask about the methods of ingredient exchange, the making and preparation, distribution and diffusion, shopping and finding new recipes and even the details of domestic life at home.

Building on the theme of recipe as signal of the future, The Center for Genomic Gastronomy just released a cookbook that looks at the future of food through the lens of recipes. It takes data from the current and historical traditions of food and food systems and uses those data to construct food and recipe artifacts of the future. Not only does it persuade, it provides context for what different ingredients mean to cuisine, culture, and habitat. One of the significant themes of the book is that it draws out how so many of our food histories have been aesthetic as much as they have been functional. And the graphical presentation is spot on.

These kinds of presentations and analytics also pave the way for automated preference aggregation, and as we discuss how computing and Internet technologies affect how we find new information and discover new combinations, these kinds of analytical approaches are going to become more common in our everyday lives. As my voice-activated mobile device starts to suggest what to make for dinner, I'm very interested in the assumptions it uses to make those suggestions. This is where culture gets hard-coded into the algorithms, but it's also an opportunity to accelerate culture by leaving some leakiness in the indexes and letting some not-so-alike ingredients blend over and mix with others.

Food was the first technology, and it's always been our social adhesive. Now we can go from asking what we should have for dinner to asking what we can have for dinner. According to my new decision support cookbook, catsup, beer, fava beans, and saltines, when prepared well, can be an excellent feast.