Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Power Up and Evolve: It's Not Just for "Pokémon"

The surprising ways augmented reality games affect our brains and bodies

In early July, “Pokémon Go” burst onto the smartphone screens of people around the globe seemingly overnight. Within the first week of its release, the game had more daily users than Twitter and more installs than Tinder or Snapchat. Within three weeks, 75 million people around the world were playing it every day—making it not only the fastest growing app in the world, but the fastest growing product in human history.

In early July, “Pokémon Go” burst onto the smartphone screens of people around the globe seemingly overnight. Within the first week of its release, the game had more daily users than Twitter and more installs than Tinder or Snapchat. Within three weeks, 75 million people around the world were playing it every day—making it not only the fastest growing app in the world, but the fastest growing product in human history.

In terms of sales and cultural impact, “Pokémon Go” is an undeniable coup for its creators—and for context-aware, augmented-reality gaming in general. But there’s a more important way to measure its success: in human well-being.

A staggering third of all players reportedly count weight loss among their motivations for playing—and data collected by major news outlets indicate they have been wildly successful. I crunched the numbers with my math friends on Twitter and we estimated that people playing “Pokémon Go” were collectively losing 571,000 pounds a day. And that’s not all. While it’s harder to quantify, major mental health benefits are being reported as well—particularly for kids with autism and people who suffer from chronic social anxiety and depression.

I’ve spent the last 15 years researching the psychology of games and their potential to help us become the best version of ourselves. So watching all this unfold was surreal. It felt like this dream I had for so many years had, overnight, become a shared reality for millions of people worldwide.

I’ve spent the last 15 years researching the psychology of games and their potential to help us become the best version of ourselves. So watching all this unfold was surreal. It felt like this dream I had for so many years had, overnight, become a shared reality for millions of people worldwide.

Of course, the game’s impact isn’t without some negative aspects. We’ve seen concerns about privacy and safety, and friction over players not respecting real-world sacred contexts like cemeteries, churches or memorials. But seeing the game emerge as this sudden engine for happiness and health that people find easy to embrace has been like a little bit of utopia in the summer of 2016 for me.

Thanks to the success of “Pokémon Go”, millions now believe that “gamification” does work. But many don’t necessarily knows why it works. So I’d like to break down what “Pokémon Go” does to our brains and bodies—and what it, and games like it, will need to do to sustain success.

Breaking the Brain’s Resistance to Exercise

Part of how “Pokémon Go” helps motivate exercise has to do with the “ventilatory threshold,” the point during exercise where there’s less oxygen coming into your lungs than there is carbon dioxide going out. Everyone crosses this threshold when they exercise, but we don’t all process it the same way. For roughly half of us, we experience it as pleasurable. We release endorphins and get a “runner’s high.” But for the other half of us, crossing this point triggers alarm bells in the brain: “Hey! You’re running out of oxygen! Stop doing that! You’ll die!” Although this isn’t true—the body is still getting plenty of oxygen—this over-reaction naturally creates an anxious and unpleasant feeling. Our bodies tell us to stop before we can really benefit from the exercise. The key for these people is to figure out how to override their bodies’ over-reaction to exercise. And the best way to do this is to get the brain more excited about something it wants than what it doesn’t want (to run out of oxygen and die).

That’s where a game can help. The reward center of the brain, which is involved in all forms of goal-oriented behavior, lights up whenever you anticipate something good happening. It releases dopamine into your bloodstream, which sends a signal to your body that it’s okay to keep pushing yourself. And “Pokémon Go” is essentially a nonstop dopamine trigger—all in the context of physical exercise. That’s because the game ensures that something good, like collecting a new creature or a valuable resource, can happen anywhere, anytime.

In “Pokémon Go”, you obtain Pokémon creatures and special “power-ups” by walking around the real world. An in-game map screen of the world around you shows you their general location. Additionally, you can get rare creatures from Pokémon eggs, which require you to walk up to 10 kilometers before they hatch. By putting abundant rewards within a reachable distance, “Pokémon Go” creates a nearly continuous flow of opportunities, which means that you’re constantly sending more blood to the brain’s reward center. It’s the ultimate state of goal orientation.

In “Pokémon Go”, you obtain Pokémon creatures and special “power-ups” by walking around the real world. An in-game map screen of the world around you shows you their general location. Additionally, you can get rare creatures from Pokémon eggs, which require you to walk up to 10 kilometers before they hatch. By putting abundant rewards within a reachable distance, “Pokémon Go” creates a nearly continuous flow of opportunities, which means that you’re constantly sending more blood to the brain’s reward center. It’s the ultimate state of goal orientation.

People who “hate exercise” but want to do it anyway are finding that “Pokémon Go” is helping them tune out their brain’s reaction to the ventilatory threshold and tune in to the pleasures of physical movement. This is the first app that allows you to basically hack your own neurological response to exercise!

Reversing Depression’s Pathways

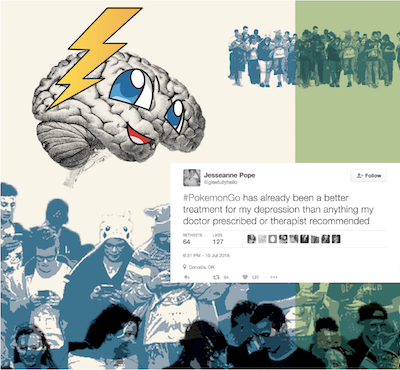

If you do a quick search for “pokemon go” and “mental health” online, you’ll find numerous articles compiling people’s social media posts declaring how much the game has helped them. Posts likes this: “‘This is actually making me want to leave my room and interact with people after years of depression.” “This game has helped me get out in the world and do things that are scary to me more than any prescription or therapy I’ve tried.” “My son, who has autism, is exploring more and feeling confident in different environments than I’ve ever seen.” For them, this gameful change is not baby steps. It’s leaps. What’s driving the leaps?

As 19th century author G.K. Chesterton once said, “There is one thing which gives radiance to everything. It is the idea of something around the corner.” “Pokémon Go” offers up such a world. Every city block is a chance to discover a rare and wonderful creature. Every corner is a place to meet a new ally. Every building and park is full of abundant resources that you need to get further in the game. Strangers who pass by are most likely in on the secret of the game, and can point you to the power-ups you need. In this way, the game teaches your brain to remember: Something good can happen. I have the power to achieve my goals. Others are here to help me. These are things that are difficult to remember when we suffer from anxiety or depression. At a neurological level, the regions of the brain associated with hope for the future, self-efficacy, and goal achievement become chronically underactivated and even shrink over time. A game like “Pokémon Go”, particularly if it is played for an hour or more a day, can help reverse this neurological deficit. Every time you achieve a goal, you retrain your brain to believe that positive outcomes are not only possible, they are within your own control.

The abundance of the “Pokémon Go” world makes it a particularly positive social context, where anxiety or self-confidence can be overcome. There is virtually no scarcity in this game. If a rare creature is nearby, you don’t have to compete to collect it. Anyone nearby can get their own. The same is true for all resources in the game. And since there’s no scarcity, the other players are not your competitors; they’re your community. And that makes it an opportunity for abundant positive real-life social interactions.

The game even has a feature that allows you to lure Pokémon—and therefore other players—to a specific location, which often creates an instant crowd gathering to catch the creatures. This has the potential to not only impact the health and well-being of individuals, but make whole communities more connected. Shortly after the launch of “Pokémon Go” I was giving a talk at the HomeSchool Association of California. Virtually everyone in the audience, parents and kids alike, had been playing “Pokémon Go” in the preceding weeks. Afterwards, the grandmother of one of the students came up to me to say, “You know what the best part of the game is? I’m talking to teenagers every day because I’m out walking around, playing “Pokémon Go”. Teenagers are talking to me!” Lack of generational interaction and depression in older generations is something many of us care about, but don’t necessarily take action on. But “Pokémon Go” serves as a platform that makes it effortless.

The game even has a feature that allows you to lure Pokémon—and therefore other players—to a specific location, which often creates an instant crowd gathering to catch the creatures. This has the potential to not only impact the health and well-being of individuals, but make whole communities more connected. Shortly after the launch of “Pokémon Go” I was giving a talk at the HomeSchool Association of California. Virtually everyone in the audience, parents and kids alike, had been playing “Pokémon Go” in the preceding weeks. Afterwards, the grandmother of one of the students came up to me to say, “You know what the best part of the game is? I’m talking to teenagers every day because I’m out walking around, playing “Pokémon Go”. Teenagers are talking to me!” Lack of generational interaction and depression in older generations is something many of us care about, but don’t necessarily take action on. But “Pokémon Go” serves as a platform that makes it effortless.

I had a similar experience myself. De facto segregation is something I care deeply about, but normally, I wouldn’t just approach a group of six black teen boys on the sidewalk. However, when we’re all playing “Pokémon Go”, I suddenly have a reason to. I’ve interacted with more teenagers of color wandering around the San Francisco Bay Area in the months since this game came out than I have in the previous decade.

Bringing Our Actions Into Alignment With Our Values

Numerous surveys reveal a huge gap between our values and goals—whether it’s getting more exercise, spending time with your kids, getting outdoors, or meeting new people—and what we actually spend our time on. Game design presents us with an opportunity to create a special ecosystem that empowers us to take actions that align with our self-identified values.

And the designers of “Pokémon Go” seized this opportunity, wonderfully. They created the game knowing that people have a goal of getting more physical activity. And they’ve been taking deliberate design actions to ensure the game stays in alignment with this goal, for instance, by tweaking the rules to make the game less effective if you’re riding in a car. Ultimately, that will really be key to sustaining the game’s success, or replicating it with new games. Of course, there are other factors— the game needs to grow and be dynamic to keep players from habituating and getting bored. And character and story are important too—having an already beloved intellectual property (“Pokémon” has been around since the mid-1990s) gives the game pre-existing reward triggers, instant scale, and guaranteed community, thanks to a massive fan base. The lesson here is that a game can have these and any other asset you can imagine, but how we end up feeling about it in the long run depends on if it successfully aligns with our pre-existing values—and lets us take action on them. We don’t want to play just any game. We want to play with purpose.

And the designers of “Pokémon Go” seized this opportunity, wonderfully. They created the game knowing that people have a goal of getting more physical activity. And they’ve been taking deliberate design actions to ensure the game stays in alignment with this goal, for instance, by tweaking the rules to make the game less effective if you’re riding in a car. Ultimately, that will really be key to sustaining the game’s success, or replicating it with new games. Of course, there are other factors— the game needs to grow and be dynamic to keep players from habituating and getting bored. And character and story are important too—having an already beloved intellectual property (“Pokémon” has been around since the mid-1990s) gives the game pre-existing reward triggers, instant scale, and guaranteed community, thanks to a massive fan base. The lesson here is that a game can have these and any other asset you can imagine, but how we end up feeling about it in the long run depends on if it successfully aligns with our pre-existing values—and lets us take action on them. We don’t want to play just any game. We want to play with purpose.

FUTURE NOW—When Everything is Media

FUTURE NOW—When Everything is Media

In this second volume of Future Now, IFTF's print magazine, we explore the future of communications. In our research process, we traced historical technology shifts through the present and focused on the question, “what is beyond social media?”

Think of Future Now as a book of provocations; it reflects the curiosity and diversity of futures thinking across IFTF and our network of collaborators. It contains expert interviews, profiles and analyses of what today’s technologies tell us about the next decade, as well as comics and science fiction stories that help us imagine what 2026 (and beyond) might look and feel like.

For More Information

For more information on IFTF's Future 50 Partnership and Tech Futures Lab, contact:

Sean Ness | sness@iftf.org | 650.233.9517