Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Podcast: Propaganda Primer for Post-War on Terror America

Propaganda, American Style: A Khrushchev's Perspective.

by IFTF Research Fellow Mary Kay Magistad; reposted from Whose Century Is It? on PRI

Nina Khrushcheva, great-granddaughter of former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, teaches propaganda at the New School in New York.

Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

We are the stories we tell ourselves, as individuals and as societies. Which stories to tell and how to tell them, are choices. When people in power tell them, to build cohesion or support an agenda, you could call them propaganda.

“America is very sheepish about admitting that it is engaged in propaganda, because ‘we tell the truth’ or ‘we do whatever we do for the sake of democracy,’” says Nina Khrushcheva, great-granddaughter of former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushcheva, a professor of international policy at New York’s New School and a US citizen, who has lived in the United States for 25 years. “It's others who are engaged in propaganda. The same thing was with the Soviet Union. It's the Americans who propagate, it's the deceiving West. ‘We are the ones who actually tell the truth.’”

US soldiers from Viper Company (Bravo), 1-26 Infantry walk during a patrol at Combat Outpost (COP) Sabari in Khost province in the east of Afghanistan on June 22, 2011. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

US soldiers from Viper Company (Bravo), 1-26 Infantry walk during a patrol at Combat Outpost (COP) Sabari in Khost province in the east of Afghanistan on June 22, 2011. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

Khrushcheva remembers the shift of rhetoric that occurred in her adopted country immediately after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the sudden appearance of Orwellian terms like “Homeland Security,” “War on Terror” and “Enhanced Interrogation.”

“I'm reading the news, and thinking, ‘oh my God. You have no idea what's happening to your country,” she recalls. “I mean, I felt like as a good Soviet, charitable Soviet, ‘you don't know what's happening to your country. You cannot read between the lines. You have no idea what it is.’

So she started teaching propaganda at the New School. She challenges her students to be aware of who’s trying to shape their perceptions, and why, of what they carry with them subconsciously.

“Because I think it's an important skill to have, because it's humbling for my students, especially my American students,” she says. “I have a lot of foreigners in this class. And so, it’s is very important to see comparisons of how other countries see us, and how other students see America, and how many American students see other countries and what kind of cliches there are. ... We are not aware that a lot of those perceptions are sound bites of a country created by various bigotries or political agendas or something. And I think the awareness is something that we all should strive for. We're not going to get better, but at least we know that we are imperfect.”

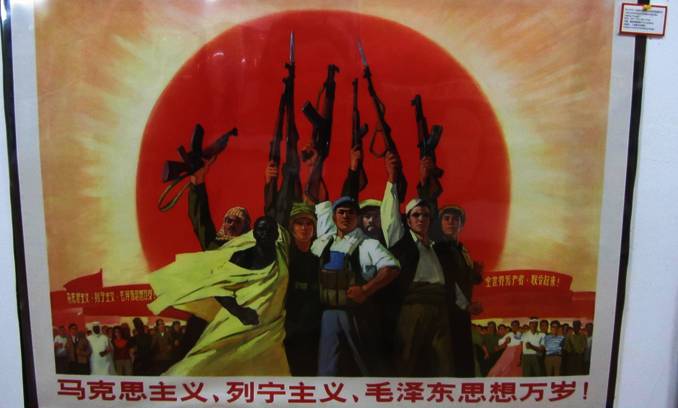

A poster from Shanghai's Propaganda Museum. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

The word “propaganda” might bring to mind socialist realist heroic images, and outlandish claims of glory. And, that’s one form of it. But propaganda can mean a number of things. One definition is, simply, spreading information in support of a cause. Another is, information that is not impartial, presenting facts selectively, using loaded messages to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information presented. Yet another definition is distorting information, or spreading information, to further an agenda, such as to achieve or retain power, or to make people act in a certain way.

“There are all these formulas that propaganda uses, Khrushcheva says. “You create a public perception and then you don't need to prove anything anymore. Or you can have propaganda by omission. Or you can have a few true statements, and then segue into an untrue statement. And it happens everywhere. It happens all the time.”

It happens in US presidential elections.

“Donald Trump is brilliant at appealing to emotion,” Khrushcheva says. “I mean, he has emotions, horrible bigoted emotions we spent so many centuries trying to get rid of… In some strange way, he empowers people to be bigoted and racist and horrible to each other, and sort of changes the whole formula of behavior.”

That counts as propaganda, broadly defined. A more direct example, she says, is how the Bush Administration in general and, she believes, Vice President Dick Cheney in particular, shaped the rhetoric in the post 9/11 world, with increased surveillance and reduced civil liberties at home, and outsourced torture abroad. Years later, after the Senate report on enhanced interrogation came out in 2014, with the findings that it hadn’t been effective, Cheney insisted on NBC's “Meet the Press” that it had, in fact, been effective, and that it didn’t bother him that one out of four of those detained and tortured were innocent, as long as the "bad guys" got caught.

A Dick Cheney mask and other items at Nina Khrushcheva's New School office. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

A Dick Cheney mask and other items at Nina Khrushcheva's New School office. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

“He’s like a black orchid,” Khrushcheva says. “He’s an absolute oxymoron of democracy, and yet he turned the vice presidential job, which is an irrelevant job to a degree, into one of the most important jobs in the world." What's remarkable, she says, is that this happened in a political system in which checks and balances were supposed to prevent unorthodox concentrations of power.

Khrushcheva says she wishes more Americans develop propaganda literacy, that they learn to recognize when and why someone in power or who wants power is playing on their emotions, and to think before being swayed.

Wall of dictators in the office of New School Professor Nina Khrushcheva. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

Wall of dictators in the office of New School Professor Nina Khrushcheva. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

“I think we all have to be aware that it exists everywhere,” she says. “We have to be aware that nobody is spared, that if you think you know it all and you're cynical and you are sarcastic, you're still as attuned to propaganda as the next guy. I mean there's a threshold. Sometimes it's high sometimes it's lower.

“But another problem is Americans who don't think enough that foreign affairs matter. They matter tremendously. And for policies like invading Iraq and Afghanistan, it’s important to think (of the consequences) 10 years in advance. For that, you actually need to know something. Because the refugee crisis in Europe, ISIS … these are the consequences of foreign policy decisions that were made earlier on, without sufficient knowledge.”

Interested in learning more? Listen to the podcast.

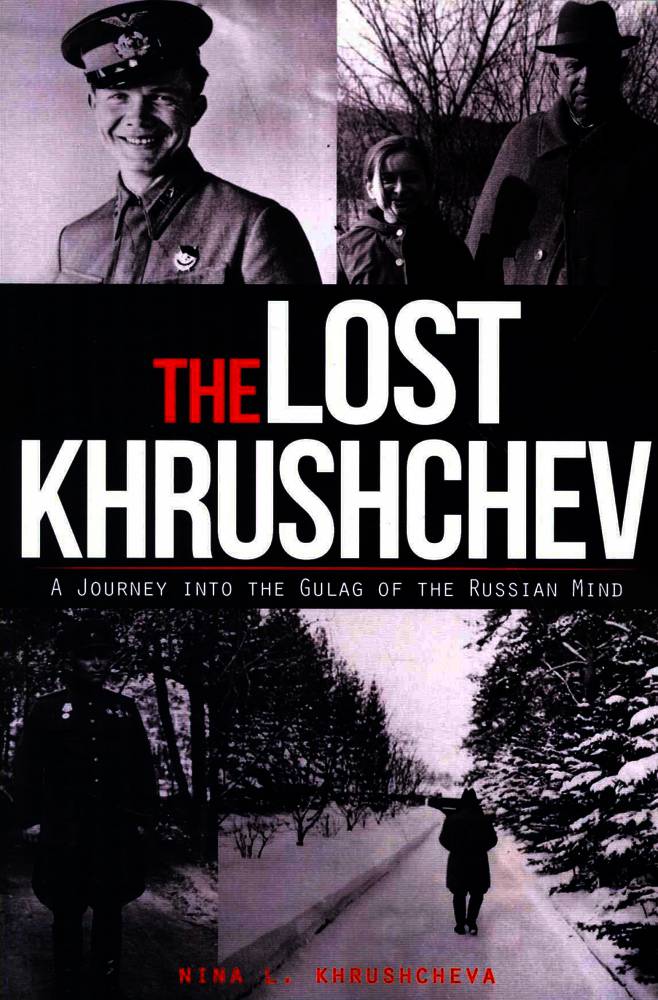

Nina Khrushcheva's book, "The Lost Krushchev," chronicles her quest to learn the truth about the death of her grandfather Leonid, Nikita Khrushchev's son, who went missing-in-action, presumed dead, on his first day as a fighter pilot in World War II.

"The Lost Khrushchev," book cover. Credit: Mary Kay Magistad

Mary Kay Magistad, IFTF Research Fellow and recovering foreign correspondent, is creator and host of the “Whose Century Is It?” podcast, a coproduction with PRI/BBC’s The World, exploring ideas, trends & twists shaping the 21st century. It’s available on iTunes, most podcast apps, and at pri.org/century.