Future Now

The IFTF Blog

Digital Music's New Freemium Model

You know when you fall madly in love with a super local musician? Their sound just captures your spirit to a tee. You love it when you go to a local joint and the DJ plays them, sometimes you even get to see them perform live. When new tracks come out, you go to a local music shop and get them to burn you a CD or add their songs to your MP3 player. Then you move to another part of the country and no longer have access to their sounds. Try as you might, local shops just don’t sell them, don’t even know about them. Forget about Spotify, local musicians don’t have access. Plus, internet access is typically too slow for proper streaming connection, and your favorite artist is unable to maintain their own music portals online. This may seem like an odd problem for those of us reading this from the US or Europe, but it’s a very common situation in many parts of the world.

In the scenario described above—which is incredibly common in places like South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, and other places with robust local music scenes and very poorly structured music industries and regulations—the artists rarely get paid for their sales. Local music shops burn pirate copies of new music and sell it without any money ever getting back to the artist.

So, what do we do? How do you provide local music to music fans, no matter where they are? How do you build a system where local musicians can actually get paid for their music?

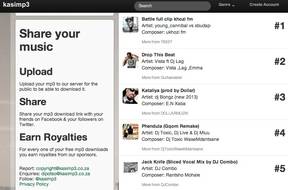

Simple! Build an ad-supported freemium platform where ANY artist can upload their music for free downloads. Set up a revenue model where artists can earn a percentage of the ad revenue based on the amount of downloads for their songs. Name it kasimp3.

Simple! Build an ad-supported freemium platform where ANY artist can upload their music for free downloads. Set up a revenue model where artists can earn a percentage of the ad revenue based on the amount of downloads for their songs. Name it kasimp3.

Doing things without money has become a big theme at IFTF in recent years. As has the importance of building a movement—not just a project or a business—in order to thrive in the socialstructed world described in Marina’s book, Nature of the Future: Dispatches from a Socialstructed World. Making sense of what this really means can be a bit tricky. It feels very foreign. But Mokgethwa Mapaya built kasimp3 on these exact principles. In an interview with HumanIPO, Mapaya had this to say about finding VC funding:

I like the romance of making [kasiMP3] from nothing, I know history is watching all my moves, so I’m very strict when it comes to taking the easy way out. I thought of asking for funding before, but it often makes me feel like I’m cheating, and I would then opt to do best with the little I have.

The other thing I don’t like about involving “capitalists” is that it automatically simplifies kasimp3 into a business instead of a movement for change.

kasimp3 takes the freemium model and expands it to the music industry, massively increasing access to local musicians and fans at the same time. Mapaya may very well be disrupting the entire music industry in the long run. To date there are upwards of 40,000 artists from throughout Africa and parts of Europe and Asia that have signed up to kasimp3, giving them a vastly broader audience than before.

In July the site had over 500,000 unique visitors. That’s already up from just under 280,000 in April. In May, kasimp3 announced a new partnership with South Africa’s Metrorail, a train system that transports approximately 4 million passengers a day. The partnership will bring the kasimp3 platform onto Metrorails mobile app, GoMetro. And for an average train commute time of 3.2 hours a day, free music from over 40,000 artists is a welcome addition.

What does this mean for the future?

A few things…

• Platforms like KasiMP3 may revitalize local music industries, propping up development efforts in the mean time. Here’s why. kasimp3 gives free music to fans and provides income to small local artists. There is simply no limit to demand or supply in this model. The fact that the music can be downloaded, eliminating the need to listen to very annoying commercials while streaming, is a mega bonus further decreasing the need to illegally download free music and removing any limit to demand. Of course, supply is endless too. In fact, kasimp3 may be the first way many musicians earn money on their recorded music. The World Bank has been working on solving this problem in West Africa—a place with an exceptionally robust local music scene that has been destroyed for lack of proper revenue models for musicians—for a while. You can read about their work in the brilliant book, Poor People’s Knowledge: promoting intellectual property in developing countries.

• As “world music” (a rather ridiculous name for music that is non-western, defining everything else as the “other”, but I digress) continues to grow in popularity, platforms like kasimp3 may begin to replace more commercial music ventures. Small local artists who become viral might even begin to replace artists like Jay Z, who had to resort to some rather outlandish commercialization with his recent Samsung app in order to reach more fans. Given the option, music lovers will always search for what we define as authentic artists. Or is this just my preferred future?