Future Now

The IFTF Blog

California’s Cap and Trade System: A Choice for Making the Future

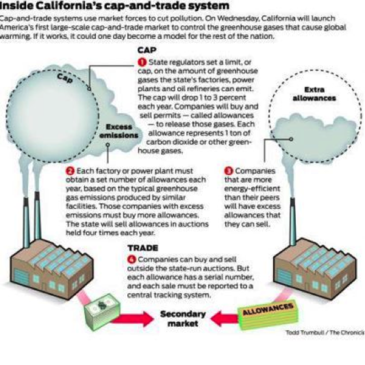

With the launch this week of its cap and trade system, California’s state leadership demonstrates great foresight and a proactive approach to shaping our future. Passed in 2006, the California Global Warming Solutions Act (AB32) aims to reduce greenhouse gasemissions through the trading of allowances by polluters.

On Wednesday, November 14, 2012, the first allowances were auctioned. Companies received 90% of their allocated permits for free in this first round. As companies innovate and find new ways of reducing their emissions, they can sell their excess permits to other polluters for a profit. Over time, the total number of permits will fall in number. (See diagram illustrating the system from the San Francisco Chronicle. See Smithsonian for surprising history of cap and trade.)

California has a history of embracing the future. The week before, California voters supported Prop. 39 and the establishment of a new state fund to support the adoption of clean energy technology, the Clean Energy Job Creation Fund. Half the revenue generated (up to $550 million) by the closing of tax loop holes will fund energy efficiency retrofits and renewable energy systems in public facilities, provide financial and technical assistance for retrofits, and provide job training in these fields for veterans and disadvantaged youth. The other half will go into the state’s general fund.

In reference to the success of Prop. 39, Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board, the agency charged with implementing the state's cap-and-trade system, explains, "We put our money where our mouths are. We back up what we do in regulation by shifting subsidies from things that pollute and are inefficient to things that are more efficient and make our state more resilient.” The California experience demonstrates that with our forward-thinking policymakers, business leaders and residents, we can become more adaptive to our changing circumstances and drive change in a positive way.

In general, when our context changes, we are always faced with the dilemma of shifting our trajectory. Given the formidable change underway, the way we’ve done things in the past is no longer appropriate for our new set of circumstances (i.e. climate change, growing global demand for resources, etc.). The battle over what to do about climate change is a choice between denial of our changing context and a proactive approach to shaping the future.

There are two curves: the descending incumbent curve and the ascending emergent curve. The incumbent curve is inherently descending because as our context changes, what worked in the past is likely to work in a different set of circumstances. The ascending curve is the future – we know it’s there, but it is less clear than what we know. Typically, our movement from the incumbent to the emergent curve is dictated by how we perceive the immediate costs and the movements of our competitors.

The two-curve model was originally conceived by Ian Morrison, past president of IFTF, in his book, The Second Curve. While Ian’s book focuses on the business, changing markets, and the risks of changing your business model, in the context of climate change, the two-curve model is useful. The urgent need to shift to the next curve is clear (see vast field of climate science). The means for doing so are diverse and many options are clear, while many others are still emerging.

The incumbent curve represents business as usual. It is the fossil fuel economy. Centralized energy generation is the reigning model, based on large-scale systems and centrally controlled distribution. Pollution is considered an externality and not part of the balance sheet. But the context is changing. As global demand continues to rise, prices will also continue to rise. As environmental conditions worsen, new constraints will be put upon these resources as governments realize the costly impacts of fossil fuel combustion on public health, our built environment and the economy.

The emergent curve represents early adaptation to the changing context. While it is an uncertain place, in the area of energy and climate disruption, there are some clear options in technology, public policy, and adoption of new practices. Energy, and resource efficiency gains more broadly, can be achieved across the economy from production to consumption creating both economic and environmental gains.

The incumbent curve can be seductive. It’s the reality we know. It’s where a lot of money has already been made. Ask the California Chamber of Commerce who attempted to halt the launch of the allowance auction this week. And then also this week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) announced that as a result of new drilling techniques, the U.S. is forecast to become the world’s top oil producer by 2017. Although this prediction assumes that oil prices will remain relatively high and that new sources will be discovered after 2020, this possible future allows for incumbents to hold on to their familiar business models while continuing to down play climate change.

In addition to climate change, increasing the production of oil and gas as is predicted by the IEA will require an 85% increase in water consumption at a time when freshwater resources are diminishing as a result of growing global demand. For the first time, the International Energy Agency’s World Outlook 2012 includes a chapter on water. (Watch the interview with IEA Executive Director, Maria van der Hoeven.)

With California’s cap and trade system now in place, it is estimated to generate $1 billion from the sale of permits. The question now is what to do with this new revenue? The law specifies that revenues go into a special greenhouse gas reduction account and that programs receiving funds align with the goals of AB32. Next 10, a California nonpartisan nonprofit, recently sponsored a research series exploring the state’s options for how to use the allowance value generated by cap and trade. According to the findings, the greatest economic benefit would come from new energy efficiency programs.

Faced with this propitious opportunity, how will our state leadership and residents choose to shape the future? Will we use the new revenue to plug our momentary budget gaps or invest wisely in driving our shift to the Next Curve, the new energy economy?