Future Now

The IFTF Blog

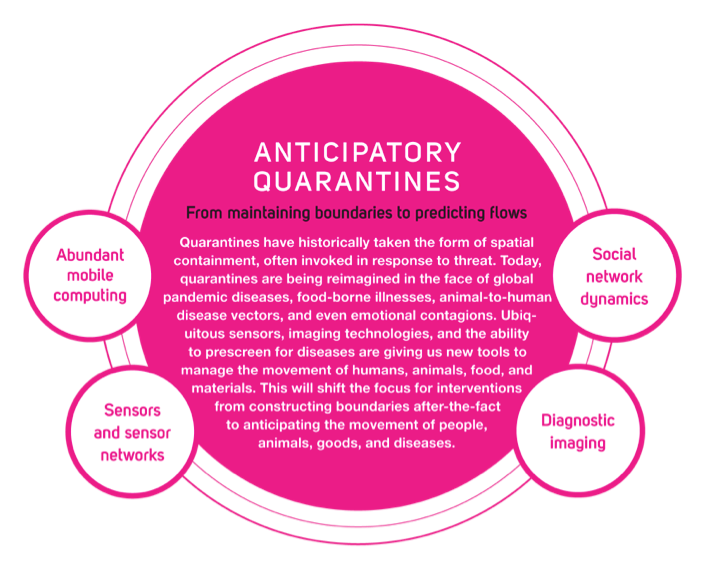

Anticipatory Quarantines

It’s exciting to think of the world as a highly connectedplace, where people, goods, and ideas spread easily and freely to the larger global population. Through Twitter, you can hear about what is happening on the ground during a protest in a city thousands of miles away, and through the expansive network of international air travel, you can be on another continent within hours of leaving your home. Of course, not everything nor everyone travels freely to everywhere they’d like to go, and not every idea moves seamlessly, but, for the most part, it feels like each year, we have more exposure to people, places, goods and ideas from all over the globe.

Of course, the underbelly of a highly connected globe is that not only do people, goods, and ideas travel, but so do pathogens and disease vectors that lead to food-borne illnesses, zoonotic outbreaks, and global pandemic diseases. Historically, we have attempted to stop the movement of contagious diseases by isolating those infected. The practice of quarantining, or the forced physical separation to protect one from another, has been a public health intervention strategy as far back as at least the Black Death. In fact, in the 18th and 19th Centuries, quarantines were, as Univeristy of Pennsylvania historian David Barnes explained, "an unpleasant fact of life" in most port cities.

But in today’s globally connected society, what we know is that it is no longer enough to try to physically isolate infected people or goods. Boundaries have never been more porous, and the pace and scope of the movement of people and goods is too fast and too far-reaching in many cases to try to contain. So, when thinking about our health and well-being in the future, we need to consider that effective quarantining, whether it’s of people, animals or foods, is re-emerging today as an issue of urgent biological, political, and even architectural importance. The question is, then, how do we quarantine in the 21st Century?

The forecast Anticipatory

Quarantines, which sits at the intersection of environments and tools on Health Horizons’ 2010 Map on the Future of Science, Technology, and Well-being, suggests that over the next decade, we’ll shift the focus from creating boundaries after-the-fact to anticipating the movement of people, animals, goods and disease. By extending the reach of traditional surveillance systems and medical records, such as hospital intake forms and death registrations, a more open, participatory approach to pandemic prevention will improve our ability to identify an outbreak at the local level and contain it before it spreads. Digital epidemiology will be able to mine what Stanford University’s Nathan Wolfe calls “viral chatter” and identify where nascent outbreaks may be forming. Using mobile phones, people in viral hot spots will be able to report warning signs of zoonotic outbreaks, such as suspicious human and animal death.

Researchers like Dr. Nathan Wolfe and his Global Viral Forecasting Initiative at Stanford University are key signals supporting the forecast of anticipatory quarantines. GVFI researchers are trying to flip our entire approach to pandemics on its head. They have created an early warning system that will enable us to prevent pandemics in the future, and they liken it to when we figured out that it was better to prevent heart attacks than to try to treat them, after the fact. They want to treat outbreaks before they spread.

The Economist sees the work and ideas behind GVFI spreading, explaining, “The idea that we must not only respond to pandemics, but work to predict and prevent them will move beyond a small group of advocates and become a mainstay of some of the world’s largest governments and foundations. The world will increasingly recognize that in the case of pandemics, as with heart disease and cancer, an

ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The early warning system Dr. Wolfe and his team have set up now operates in Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, China, Malaysia, Sierra Leone, and Gobon. It is absolutely reliant on the availability of mobile phones, which are used to monitor and collect data and communicate findings to central research hubs. And, over the next decade, as mobile technologies get smarter and cheaper, they will continue to be critical tools for anticipatory quarantines; they will support our ability to anticipate outbreaks before they spread.