Future Now

The IFTF Blog

The Future of Food: Creating an Open, Shared Food Web

![]() **This post is also featured on Food+Tech Connect.

**This post is also featured on Food+Tech Connect.

"One thing we love about cooking is how adaptable and constantly changing it can be. For example, think of inheriting your grandmother’s cherished tomato sauce recipe. You’ve tweaked the recipe slightly to suit your tastes, then passed it along to a few friends who have added their own spins to the sauce — say, a little more garlic or a spicy addition. Just like Github did for open source software, there’s space for technology to create a canonical source where one could view changes and updates to recipes."

In their contribution to Food+Tech Connect’s recent Hack Dining event, Food52 Co-Founders Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs advocated for a GitHub approach to home cooking, a way for cooks to track changes to recipes and build on each other’s ideas. Think of it as a collaborative and dynamic global cookbook, created by everyone from a Michelin starred chef to a student learning to eat on a budget.

The ability to connect the digital and physical worlds gives us opportunities to link people, skills, and knowledge together in ways we've never seen before. Indeed, when our 2014 Ten-Year Forecast set out to imagine ten projects that would change our paradigms in the next ten years, we included a Wikipedia for Making, a universal grammar for making anything.

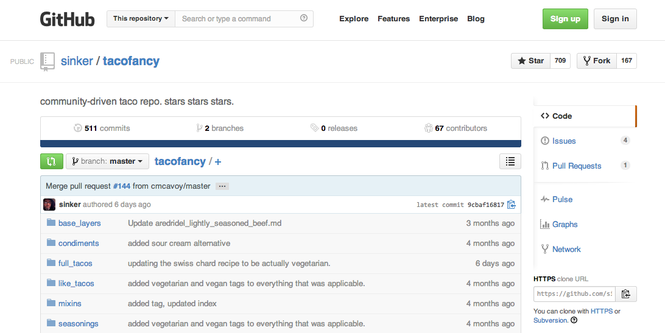

By sharing code and tracking adaptations in a standardized format, GitHub fundamentally changed the way people interact with code. It created a shared grammar for the many programming languages housed in its nearly 14 million repositories. Now the open-source, collaborative approach is starting to reshape how we organize materials, resources, and knowledge to make objects in our everyday lives. GitHub includes repositories for things like this taco recipe—which currently has 67 contributors—perhaps a precursor to the larger shift in home cooking Hesser and Stubbs propose. [Update July 10: In answer to their challenge, Github user wubbahead created gitchen.org, a single place for the platform's cooking repositories.]

Top chefs understand the potential of codifying cooking. Ferran Adriá closed his elBulli restaurant to launch the elBulli Foundation, which is creating BulliPedia—a shared archive of culinary knowledge that aims to stimulate creativity. Adriá believes that the cuisine of the past 50 years has evolved so much that it requires a new coding, a Cuisine Genome, to track flavor combinations, techniques, and technologies for cooking. Led by "the most influential chef of our time", this top-down effort from gastronomy's most brilliant minds combined with bottom-up sharing of recipes from home cooks represents a transformation in the ways we interact with culinary knowledge.

The signals of an open-source, codified model extend beyond the kitchen to the entire food web. Learning from its own difficulty interpreting and complying with USDA standards, Wisconsin’s Underground Meats crowdfunded an open-source guide to meat curing safety standards. Produced under a Creative Commons license, the guide will be modifiable by anyone, and will include instructional videos to share production processes.

Imagine a universal grammar extended to check recipes against food safety compliance and regulation—a mashup between a cookbook and regulatory code. We could track the number of times someone builds on a process, discover gaps in regulation, or study ingredient nuances to assess local availability or cultural differences. Turning processes into a shared resource would reduce complexity, create new alliances throughout the supply chain, and build better feedback loops with regulators.

Another signal, the Open Source Seed Initiative, aims to build openness into the food system from the ground up. Packets of seed with a “free seed pledge” contain genetic resources that cannot be legally protected, creating a perpetual seed commons. If information about each seed was coded online and easily duplicated, tweaked, and reproduced for local conditions—and linked to repositories for processing and cooking methods—we would have a true seed-to-fork understanding of the processes by which we produce the food we eat.

Another signal, the Open Source Seed Initiative, aims to build openness into the food system from the ground up. Packets of seed with a “free seed pledge” contain genetic resources that cannot be legally protected, creating a perpetual seed commons. If information about each seed was coded online and easily duplicated, tweaked, and reproduced for local conditions—and linked to repositories for processing and cooking methods—we would have a true seed-to-fork understanding of the processes by which we produce the food we eat.

“Eating is an agricultural act,” Wendell Berry reminds us, and it is increasingly just as much a technological act. The ways in which we engage with technology to grow, cook, and eat our food will undoubtedly change in the coming years. We have the opportunity to harness technology to create truly open, shared, and cherished knowledge and resources for our global food web.

This post is part of IFTF’s food futures research, which brings systematic futures thinking to food system efforts around the world. Our long-term view encompasses multiple scales, levels of uncertainty, and radically different possible futures. We develop foresight to help others develop insight and take action toward impactful, transformative, resilient change. For more information about our research, sponsorships, collaborations, and events, please contact Rebecca Chesney at rchesney@iftf.org.